- Home

- Julia London

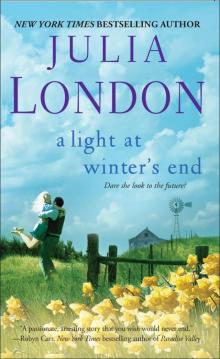

A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End Read online

“Do you want to raise Mason?” Wyatt asked.

“No, I … not exactly.…” What, in her heart of hearts, did she want? Holly could see Mason’s round little face, his blue eyes smiling up at her. “Yes. Maybe,” she confessed. “I feel so protective of him,” she said quickly. Her vision suddenly blurred. Shocked and embarrassed by even the hint of tears, Holly turned away from Wyatt.

“I understand. But he is your sister’s son.”

“I know.”

“Hey.” Wyatt stepped up behind her, put his arms around her, and pulled her close. “It’s going to be okay,” he said. “He’s lucky to have you.”

Holly was the lucky one. She turned toward him. Neither of them spoke; Wyatt’s fingers drifted across her cheek, brushed her hair back, and grazed her ear. Holly looked at his lips, recalling the kiss they’d shared yesterday. A man was the last thing she’d had on her mind when she’d come out here, but then he’d appeared in her yard, and he was so understanding of the chaos in her life …

“And I’m a lucky guy,” he murmured, and kissed her. His hand slid to her neck, his fingers curling softly around it, his mouth moving against hers.

“A contemporary heartbreaker. … London knows how to keep pages turning.”

—Publishers Weekly on Summer of Two Wishes

A Light At Winter’s End is also available as an eBook

ALSO BY JULIA LONDON

The Year of Living Scandalously

One Season of Sunshine

The Summer of Two Wishes

A Courtesan’s Scandal

Highland Scandal

Book of Scandal

The Dangers of Deceiving a Viscount

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

Guiding Light: Jonathan’s Story (with Alina Adams)

Pocket Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Dinah Dinwiddie

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Pocket Books paperback edition March 2011

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Cover illustration by Tom Hallman

Interior design by Davina Mock-Maniscalco

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-1-4516-0684-3

ISBN 978-1-4516-0688-1 (ebook)

This book is dedicated to all the women and men who have cared for children who are not their own.

a light at winter’s end

Chapter One

The cowboy rose at dawn’s first light and pulled on a pair of worn, dirty denims. “Come,” he said to his dog and, scratching his bare abdomen, which had been made lean and hard by the work he did around the ranch, he padded down the hall of the nondescript redbrick ranch house and into the kitchen.

There was something sticky underfoot on the linoleum, but since the fluorescent bulb overhead was out, he couldn’t really see. He sleepily made a note of it and thought Sunday, when he washed his clothes in that old harvest yellow washer, he might wash a few things around the house as well. He couldn’t remember ever mopping the floor here, and figured, after a year, it was as good a time as any.

He studied the row of buttons on the trendy contraption that some would call a coffee machine and he called a pretentious piece of pain-in-the-ass machinery. It was one of the few things he’d kept from his marriage. He’d bought it for her, of course, and she’d been ridiculously pleased with it. He’d never quite figured out how to operate it correctly. Why had he kept it? He didn’t know anymore. The only thing he did know was that Wyatt and Macy Clark were no more.

He punched a few buttons and the machine sounded like a locomotive steam engine. He turned away and almost tripped over his black Lab. Milo was always sneaking up on him like that, appearing underfoot, that damn tail always wagging. Wyatt had never known a happier dog, and he’d had quite a few in his life. No matter what he put the dog through, he grinned and wagged his tail and acted like he wanted more hard living.

Milo was the other thing Wyatt had kept from his marriage. Because Milo was his dog. Not hers. His.

His dog was hungry. Wyatt opened a sack of dog food he kept in a trash can next to the greasy kitchen wall. He scraped out two cups of chow and poured it into a dirty dog bowl. Milo didn’t mind that he ate from a petri dish; he had one eager paw in the bowl as he wolfed it down.

Wyatt walked back to his bedroom and found a shirt in his pile of unwashed clothes that didn’t smell too bad. Today he was going to tackle that broken fence the cattle kept trampling, and he didn’t need to be clean or smelling of roses to do that. He dressed, pulled on his boots, brushed his teeth, and ran his fingers through his black hair. It had grown kind of long, and he’d taken to wearing it in a little ponytail at his nape. Never thought he’d see the day he did that—he’d always been a clean-cut kind of guy before his world collapsed—but what the hell? He lived by himself. The only person he saw on a regular basis was his baby daughter Grace, and she didn’t care what he looked like. He didn’t have anyone to impress, and Milo would like him if he walked around naked. Which, in all honesty, he’d done a time or two.

Wyatt returned to the kitchen. The coffeemaker now showed all green lights, so he poured himself a cup and sat down at the kitchen table. There was a neat line of stuff he used every day: salt and pepper, Tabasco sauce. A stack of paper napkins next to a stack of paper plates. And his laptop, his only real connection to the outside world. Oh, he had a television hooked up to some rabbit ears so he could get football and golf, but not much else came in over the rabbit ears.

He opened the laptop and his home screen popped up, with the news and the sports scores and his personal favorite, the Word of the Day. Today’s word was chary.

Chary. Meaning discreetly cautious. As in, the gentleman is chary about voicing his concerns.

Chary.

Wyatt sipped his coffee, clicked over to ESPN.com to check the baseball scores. He didn’t see anything he didn’t already know, and closed his laptop. He looked outside. Wyatt never bothered with breakfast. He liked getting out early while it was still cool and the wind was still. He liked the sound of the morning birds before the day got too warm for them and they disappeared into the brush.

He heard a bit of whining and looked over his shoulder. Milo had finished his breakfast and was standing at the back door, ready to go out. The paint was all scratched up where Milo would claw on it when Wyatt wasn’t paying attention. Wyatt stood up, picked up his sweat-stained hat from the table, and fit it on his head.

He opened the back screen door. Milo took off, racing across the unkempt lawn with his nose to the ground. Coffee cup in hand, Wyatt moseyed on down to the barn, put his coffee cup on a shelf inside the barn next to two other coffee cups. He had three horses inside and turned two of them out to the pasture, swatting their rumps and sending them trotting to stretch their leg

s. He saddled the third. Troy, he called him, named for the great Dallas Cowboys quarterback Troy Aikman.

When he had Troy saddled, he led him out, whistled for Milo, and swung up into the saddle. The dog raced out of the brush and ran alongside Troy as Wyatt reined him around. He rode out into uncut land, through thickets of cedar and pin oaks and around prickly pear cactus spread as wide as swimming pools. His ranch was big for this part of Texas: about fifteen thousand acres, or a little over twenty-three square miles. That was a lot of fence to mend, a lot of ground for cattle and horses to cover. Wyatt had had an old pickup truck he used when the work warranted, but mostly he liked to ride.

He rode up on the southeast corner of the fence, where the cattle had gotten their big heads through and had busted through the barbed wire. He surveyed the damage: the wire would have to be cut out and restrung. He figured he’d call Jesse Wheeler to come out and give him a hand. Jesse was Cedar Springs’ resident jack-of-all-trades, a skill he’d picked up as he hopped from one woman’s bed to another, doing odd jobs to earn his keep.

Wyatt spent the morning cutting the barbed wire from the posts. It was hot as blazes by eleven, and he paused to wipe the sweat from his eyes and take a drink from his canteen. He was standing next to Troy in the shade when he heard the cars. He turned around to see a hearse turn into the drive on the adjoining property. Another car was right behind it. And another. A funeral procession was heading up to the old Fisher cemetery. Wyatt had heard the old lady who lived there had cancer, but he hadn’t heard she’d died. Frankly, between him and Milo and the big blue sky, he’d been biding his time, hoping to buy up that property when the opportunity arose.

That’s what Wyatt did. Or used to do. He used to buy and sell ranch land, sometimes put a development on it. And Wyatt Clark of Clark Properties would buy up half of Texas if that’s what it took to keep him from civilization. Since his wife, Macy, had left him for her first husband, he hadn’t felt much like being in the world, and the more land he could put between him and everything else, the better.

He squinted at the cars as they disappeared into the cedars on the drive up to that old homestead cemetery and took another swig from his canteen.

It looked like the opportunity to make some chary inquiries had presented itself.

Chapter Two

When Peggy Fisher learned there was nothing more that could be done to save her from the cancer that was eating away at her, she set about planning her funeral with a vengeance.

It was exactly what she’d wanted, thanks to her daughter Hannah. She was buried in the blue linen suit she’d picked out herself, and per her instructions, the color of the casket complimented the suit. Her cousin D.J., a welder and aspiring singer, sang “Amazing Grace,” and a funeral spray of daisies covered her grave. Mourners were kindly asked to give to the Susan G. Komen for the Cure foundation, if they so desired. Peggy hadn’t died of breast cancer—hers was pancreatic—but she’d thought breast cancer would sound better in the obituary. “No one even knows what a pancreas is,” she’d said, clearly annoyed that she should get cancer of an organ that no one understood.

There were only two pictures of Peggy at the funeral. They’d been blown up and placed on either side of the casket so that mourners in the back of the crumbling old limestone Presbyterian church with the sagging balcony could see them. Peggy had often lamented that she’d not done something with photos when her husband, Dale, had died fifteen years ago. He’d been out mowing the lawn one hot afternoon and had dropped dead right next to the roses he’d planted that spring.

“He never had much heart after Dale Junior died,” Peggy had explained to Hannah and her other daughter, Holly, when she’d delivered the bad news. “His ol’ heart finally gave out.”

Holly, her youngest, had always found this idea a little odd, as Dale Junior had been born with a hole in his heart some twenty years prior and hadn’t survived more than a few days after his birth. She thought it was more likely that her father’s ridiculously high cholesterol was the source of his demise. But Holly didn’t argue with her mother, because her mother liked things to appear a certain way to the outside world. She liked her husband to have died of a broken heart, and her daughters to be shining examples of the feminine ideal. Whatever that was.

After the funeral and the graveside service on the old Fisher homestead, where Peggy had lived forty-some years of her life, some kind soul carted her photos back to the house where family and friends had gathered to offer their condolences and to eat the food the church ladies had prepared. The two pictures were placed side by side against the dining room’s sliding glass door, blocking the view of the back lawn and the rolling pasture and cedar trees beyond.

Holly studied the pictures. She’d politely refused an offer of beans, potato salad, and ham from the church ladies, but had given in and taken the iced tea, and occasionally she felt a cold drop of condensation from the sweaty glass hit her toes between the straps of her sandals. The photos of her mother didn’t stir her numb head to any thought other than that it was only her and Hannah now. Holly was officially bereft of any emotion, having grieved the last painful months of her mother’s life. Even longer, if she thought about it. Which she did not want to do.

Her mother had fretted over which pictures to choose, finally settling on these two. The first one, taken when she was around ten, was a blurry black-and-white image of a girl in pigtails, seated on an ancient-looking bike. It didn’t even look like Peggy. “I was so happy then,” she’d said with a sigh as she admired herself as a redheaded, full-lipped kid.

The second photo was taken after Peggy had become a mother. She was laughing at whoever was taking the picture, an openmouthed, spontaneous sort of laugh. She held Holly and Hannah, who was two years older than Holly, on her lap. They wore matching green sundresses. Hannah’s auburn hair was cut shoulder-length, and she had bangs. Her blue eyes had a happy shine to them. Holly’s strawberry blonde hair was pulled back in a ponytail, but her grayish-green eyes looked somber. Peggy’s arms were wrapped tightly around her girls. When had Peggy Fisher lost her grip of her girls? When had they slid off her lap and stopped wearing matching sundresses and ponytails?

Holly guessed the photo had been taken about thirty years ago, when Hannah was six and she was four. Did her mother choose it because Hannah and Holly were young and free of the tension that had existed between them in the last several years? Was it taken before the comparisons began to be made, or had her mother already started making them? She had an odd flash of memory, of making biscuits with her mother, of her and Hannah wearing aprons tied up under their arms, standing on stools beside their mother. Holly could remember rolling the dough and then cutting rounds with the lids of mason jars. Holly, look at the mess you’ve made. Look at Hannah! Look at how neatly she’s made hers. Holly could still see Hannah’s row of perfectly formed biscuits, lined up like soldiers, spaced equally apart. And her biscuits—not quite round, not quite straight. One of them shaped like a doggie.

Why can’t you do it like Hannah?

A collective cry of alarm startled Holly from her thoughts. She looked around the two pictures to the back lawn. The sprinklers, which Hannah had insisted be installed around the lawn so that Peggy wouldn’t have to worry about the yard, had come on where a few people milled about with plates heaped with funeral food.

“I told Loren to turn the sprinklers off.”

Holly hadn’t realized Hannah was standing beside her until she spoke. She glanced at her sister, noticed how Hannah watched with weary dissatisfaction as the guests hopped awkwardly away from the sprinklers. She looked wan, Holly thought. Drawn. She never ate, she just drank tea. But Hannah was beautiful as always, impeccably dressed in a tailored black suit and a pair of killer heels. Her hair was knotted neatly at her nape and a diamond pendant twinkled at her throat. As usual, Holly felt a little dumpy next to her sister. Her shaggy hair was down around her shoulders, clipped back from her face. She wore a black sleeveless

shift and a pair of nondescript black sandals she’d picked up from Payless.

“What are you going to do with these?” Holly asked, nodding at the enlarged pictures as Hannah’s husband, Loren, rushed out to help people off the lawn and turn off the sprinklers.

“Throw them away,” Hannah said with a shrug. “Unless you’d like some giant pictures of Mom hanging in your apartment.” She smiled.

Whoa, was that a joke? Holly couldn’t remember the last time her sister had joked about anything. “I’ll pass,” Holly said, and returned her smile. But Hannah looked as if she were bored, and an awkward silence filled the space around them. The two of them had very little to say to each other these days; their mother’s illness had taken a toll on their already fragile relationship.

Holly looked past Hannah to the dining room, where the food was laid out in Corel casserole dishes. “Is there anything I can do to help you?”

Hannah shifted her expression of weary dissatisfaction to Holly. “No, thank you. Everything is taken care of,” she said, as if Holly had waited too long to ask an obvious question.

Hannah was probably still mad at her. She’d asked Holly to call the nurses at Cedar Springs Memorial Hospital and tell them about the visitation, but Holly had forgotten to do it. She’d been trying to cover as many shifts at work as she could so that she could afford to be off for several days after the funeral, and she’d forgotten to call. Only one nurse came, and Hannah blamed Holly for it.

“I’m just trying to help,” Holly said now.

Hannah’s gaze flicked over her. “I think I’ll get something to eat.”

Holly tried not to be offended as Hannah walked away. Okay, it was true that Hannah had handled everything with their mother. Everything, from the moment they’d found out about the cancer until the very end. In spite of being the office manager at a big downtown Austin law firm, it was Hannah who found the time to check on their mother every other day, driving forty miles each way out here to where they’d grown up. It was Hannah who took their mother to every doctor appointment, to every chemotherapy session, and made sure her prescriptions were filled and that she took her meds. It was Hannah who had hired the nurse to see after Mom when she grew weak but refused to leave the home she’d known all her adult life; and in the end, it was Hannah who brought Mom into Austin to live with her, Loren, and her new baby, Mason.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

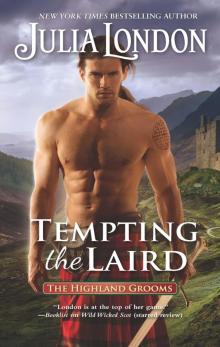

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

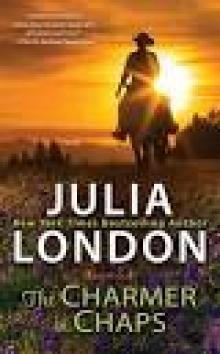

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)