- Home

- Julia London

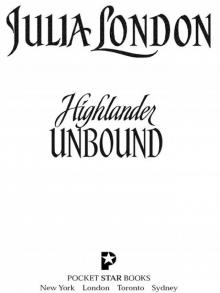

Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Read online

“I warned ye no’ to play games with a man, lass,” Liam said. “If ye play with fire, ye may be burned.”

Ellen leaned across the table, so that her gown was gaping open. “Perhaps. But if you want to touch fire, you must be prepared to hold it in your hand.”

Liam instantly made a move to his right; Ellen jumped to her left and laughed. His smile faded. “Come now, Ellie. Ye’ve had yer fun.”

“Have I?” she asked, as she ran to a window. “Shall I open the window so everyone sees how you chase me to ravage me?”

“Ye’ve no idea how close I am to doing just that,” he said, walking toward her.

Ellen pulled the heavy cord that held the drape, and let it fall. She tossed the cord on the bed and ran to the brazier. His eyes never left her; he followed her, moving slowly, a strange light playing in his eyes. “Ye’ll pay for yer foolishness,” he warned her. “I’ll no’ be gentle.”

“I do not believe I asked you to be gentle, sir…if you catch me.”

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

An Original Publication of POCKET BOOKS

A Pocket Star Book published by

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2004 by Dinah Dinwiddie

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN-13: 978-0-7434-8868-6

ISBN-10: 0-7434-8868-7

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

www.SimonSays.com

A Special Thanks

I think that perhaps when one has been in this business a while, one tends to think about the day to day mechanics of producing a book, and perhaps loses sight of the efforts of so many people that go into producing a final product. In an effort to make sure I don’t do that, I vow to take the time every now and again to think about how my dream life is really made possible. It’s not just the writing; it’s the combined effort of a lot of great people.

My special thanks to my editor, Maggie, for believing in me and showing me how to become a better writer; and my agent, Meredith, for urging me always to push the edge of the envelope. And, of course, my family, who are as enthusiastic about my career today as they were the day I sold my first book, and Louie, who keeps me grounded.

But most important, I thank the many readers out there who continue to buy my books one after the other, and write to tell me they look forward to the next. If it weren’t for all of you, I’d be living under a bridge somewhere. My dogs and I thank you—we are forever indebted to your faithfulness!

Sincerely,

Julia London

Prologue

Near Aberfoyle,

The Central Highlands of Scotland

1449

In and around Loch Chon, they would talk for many years of how the fair Lady of Lockhart laughed like a madwoman when her husband hanged her lover—on the very eve of her date with the executioner’s ax.

It was an ill wind that drifted across the Highlands in the autumn of 1449, bringing with it first the death of the obese earl of Douglas, whose heart, unable to endure the strain of his gluttony, finally gave out. In that same ill wind, his son William was swept to the title. But William, unlike his father, was fit and capable—so capable, in fact, that the mentors around the boy King James felt threatened, particularly when James, on the verge of manhood, was making a habit of refusing their sage advice. And it was in that rift between king and mentors that William Douglas did indeed see the opportunity to immortalize his power. This he did by supporting the mentor Crichton over the mentor Livingstone, which meant, that anyone aligned with Livingstone was doomed….

Unfortunately, that included Anice of Lockhart, a woman as renowned for her gentle spirit as she was for her beauty, from Loch Katrine to Ballikinrain. Given in matrimony to William’s cousin, Eoghann, the laird of Lockhart, along with a dowry of twenty sows, Anice soon discovered that Eoghann was neither seduced by her charm nor a kind or faithful husband, preferring a rough life of hunting and whoring. Nonetheless, Anice bore the feckless Eoghann five sons and one daughter. While Eoghann had no use for the latter, he adored his sons, and often left Anice and the daughter, Margaret, alone. Such a life of misery did the lovely Anice lead that it was little wonder she fell in love with the handsome Kenneth Livingstone.

Some would say that autumn’s ill wind brought Kenneth Livingstone, a warrior and a nephew to the king’s closest adviser, to the Lockhart keep. And although he was ten years her junior, one look at Anice’s lovely face and Kenneth Livingstone knew the woman he would die for.

Likewise, Anice believed she deserved this chance at love; she confided as much to her lady’s maid, Inghean, and pursued Kenneth’s love with relish, living recklessly, engaging in her adulterous affair openly for anyone to see save Eoghann, for as was his habit, he paid her little mind.

Perhaps Anice would have enjoyed her happiness for many more years had not William become the Douglas earl. Though he could not fault Anice for straying from her marriage—he knew his cousin Eoghann to be a despicable man—he could not forgive her doing so with a Livingstone. Thus her fate was sealed—William dispatched a team of envoys to his cousin’s keep to read aloud the decree of death for the adulterers.

While Eoghann did not object to William’s decree that Kenneth Livingstone should hang, he did object to the same sentence for his wife, and determined that a beheading was far more appropriate for her perfidy. But he would first imprison her in the old tower so that she might observe the construction of the scaffolding from which she and her lover would meet their deaths.

As Anice’s maid Inghean would later recall it for her grandchildren, Anice of Lockhart grew increasingly mad in that last fortnight, stalking about a cold chamber devoid of even the barest of comforts, wild-eyed and clutching a small and hideous sculpture of a beastie. Inghean would never know the significance of the ornamental statue other than to understand that Anice and her lover had shared some secret jest, and Livingstone had commissioned the thing to amuse her. The ornament was ugly—cast in gold, with eyes and mouth made of rubies so that it looked to be screaming, and a tail, braided and interspersed with rubies, that wrapped around its clawed feet.

On the eve of Kenneth’s hanging, Anice called Inghean to her. She was holding in her lap something wrapped in cloth. Slowly, she peeled away the cloth to reveal an emerald the size of a goose egg. It was a gift from her mother, she said, the only thing of value she had managed to keep from Eoghann in all the years they had been married. Anice wrapped the emerald again, and speaking low and quickly, implored Inghean to help her. She pressed the wrapped emerald into Inghean’s hands, then the ugly beastie, and begged that she take them to her brother, the blacksmith, and beseech him to seal the emerald in the statue’s belly for safekeeping. It was, she explained tearfully, her last but most important gift to her daughter, Margaret.

Inghean could not refuse a condemned woman her request. When the deed was done, she returned to the tower, just in time to watch the crowds gather for the hanging of Kenneth Livingstone. She joined her mistress on the battlements around her tower prison and stood, terrified, as Kenneth was led onto the scaffolding. Anice, unwilling to let Eoghann see her fear, cackled like a madwoman.

Then Kenneth looked up, saw Anice standing there, and Ani

ce grabbed Inghean’s hand, her fingernails digging deep as they watched the executioner wrap the noose around Kenneth’s neck. And as the executioner stepped away, Anice leaned over the battlements so far that Inghean feared she might fall, and screamed, “Fuirich do mi!”

“Wait for me!”

The executioner pulled the rope; Kenneth’s fall was quick, as was the break of his neck, and he hung, limp, his suddenly lifeless eyes staring blankly at the roaring crowd gathered before him. Anice let go of Inghean’s hand and fell back against the stone wall of the battlement, her body as limp as her lover’s.

Later, she asked for the statue and her daughter, Margaret, who was just a girl. “Heed me, lass,” she whispered when Margaret was brought to her chamber. “See this that I give ye,” she said, taking the statue from Inghean, “and promise me ye’ll guard it with yer very life!”

When Margaret did not answer right away, Anice shook her. “Do ye hear me, Maggie?” she insisted. “This that I give ye is more valuable than all the king’s jewels. When the time comes and ye fall in love, but yer father gives ye no hope for it, then ye look in the belly of this beastie, do ye ken?”

Margaret glanced fearfully at the awful little thing and nodded.

The next morning, as her husband and her two oldest sons looked on impassively, Anice knelt before the executioner’s block.

In one mean strike of the sword, Anice was sent to meet her lover.

As little Margaret grew older, the times grew more turbulent. The earl William died by the king’s own hand, and suddenly the nation was plunged into a bitter clan war. Douglas warred with Douglas and with Stuart; all alliances were suddenly suspect. Indeed, the three youngest Lockhart sons took issue with their father and their two older brothers, and made their allegiance known to the Stuarts. In the midst of that bloody clan warfare, Margaret, now fifteen, fell in love with Raibert of Stirling, who pledged his allegiance to the younger Lockharts. Margaret came to Inghean to tell her that she had given the statue to Raibert for safekeeping, that they would flee to England with her brothers. She kissed Inghean good-bye and slipped out into the night.

Inghean never saw the lass again, and in fact, it would be years before she would know that Raibert had been killed in the battle in Otterburn, and that the younger Lockharts had taken the beastie with them to England. The beastie, but not their sister, Maggie, who was left behind with a broken heart and put away in a convent by her father, where she would die a year later by her own hand.

Inghean would live for many years afterward to tell the story of the Lady of Lockhart. Yet over time her memory would fade, and she would forget the very small details. By the end of her blessedly long life, the tale of the Lady of Lockhart had come to be known as the Curse of the Lady of Lockhart, for more than one had seen the madwoman laugh at her lover’s hanging, and more than one could believe she had cursed her daughter.

When Inghean at last took leave of this world, the truth of the Lady of Lockhart took leave with her. The so-called curse was separated from fact, and grew to encompass all females born to a Lockhart. The beastie became nothing more than a prized belonging that spawned centuries of clandestine border crossings between England and Scotland by more than one Lockhart wishing to possess it, a practice that would endure for hundreds of years.

By the time Scotland was at last united with her sister England, local legend had it that a daughter born to a Lockhart sire would never marry until she “looked into the belly of the beast.” Family lore interpreted this curse to mean that any daughter born to them must face the Devil before she would marry, and the strength of that curse was bolstered by the strange fact that no Lockhart daughter ever married.

One

Loch Chon, near Aberfoyle,

The Central Highlands of Scotland

1816

A thick mist swirled around the sheepskin ghillie brogues that covered his feet, making it impossible to see where he was stepping. But stealth was imperative—he could see the French camp through the trees directly ahead and wondered how they had managed to track him all the way to Scotland. Obviously, they were still searching for him, still intent on killing him, just as they had been on the Continent.

Liam crouched down behind a tree, observing them. They had stopped for the night, lying about a small fire, one of them roasting some small animal, blessedly unaware of the danger that lurked just beyond the tree line. God, but he wished he could see his men! His Scottish compatriots were just on the other side of the French camp, waiting for him. Liam stood, tried to move again, but the thick mist prevented it, and in fact, his legs felt as if weights had been tied to them, as if he were dragging them through water.

Suddenly, to his right, a flash of color—a French soldier! Liam quickly reached for the dirk at his waist, but it was gone, dropped from the belt of his kilt. The soldier, returning from the call of nature, was startled to see him and fumbled for his pistol. His dagger, where was his dagger? There was no time to think—Liam instantly dropped to his haunches, and in one swift movement pulled the ebony-handled sgian dubh from its sheath at the top of his stocking and lunged before the Frenchman could cry out.

They fell to the ground, Liam landing on top and knocking the air from the man’s lungs as his pistol went flying into the mist. Silently and quickly, as if the man were a beast, Liam slit his throat as he had been trained to do, rolled off him and onto his feet, crouched down with his hands held before him, waiting for the next Frenchman.

What was that? A soft whistle—the bastard Frog somehow had alerted the rest of them! Jesus God, where were his men? His breath coming in heavy grunts now, Liam took one step forward, felt something whisk across his ear, and unthinkingly swiped at it. Another step, and a movement to his left caught his eye. He jerked around, could not help but gasp at the sight of the two-headed troll that faced him, the same one that—Could it be?— had haunted his dreams when he was a wee lad.

He had no time to think; the troll started for him, swaying side to side to maintain its lumbering girth. Something was pushing at Liam’s back, pushing him off balance, but he ignored it, focused only on the troll coming toward him, his hands outstretched, as if he meant to snatch him. His heart pounding, Liam gripped the bloodied sgian dubh and readied himself. Just as he was about to throw himself forward and tackle the troll, he felt a sharp jab to his bum, almost as if someone had wedged a boot—

Liam’s eyes flew open; he saw his brother Griffin standing over him, a feather in his hand, and remembered, groggily, that the war with France was over.

“Ye were dreaming again, laddie,” Griffin said matter-of-factly, and added with a lopsided smile, “I hope she was a bonny thing.”

“Ugh,” Liam groaned, and rolled over in his bed to bury his face in a pillow. “Why must ye bother me so, Grif? Can ye no’ leave a man to sleep?”

“The sun is already shining on the loch, Liam. Yer mother asks after ye, and Payton Douglas has come—did ye no’ promise him a lesson in swordplay?”

Damn if he hadn’t. “Aye,” he said, yawning, “that I did.” He reluctantly pulled the pillow from his face and blinked against the sunlight pouring into the room. He was drenched in sweat again, the result of another nocturnal battle with the French. He’d be glad when his regiment deployed and he could put his dreams behind him.

“Father is due back from Aberfoyle today,” Griffin said, crossing over to the bureau against the wall to examine Liam’s things there, “and Mother requests your presence at the supper table.” He spared Liam a glance. “She’s no’ happy with yer prowling about in the wee hours of the morning.”

Liam simply ignored that—his family did not understand his need to keep his skills finely tuned, something that could only be accomplished by practicing various maneuvers at night as well as day. He pushed himself to his elbows, watched as Griffin picked up the hand-tooled leather ornamental sporran he had purchased from a leathersmith near Loch Ard. “I’ll thank ye to put it down,” he said as his brother

peered inside.

With a chuckle, his brother obliged him by tossing the leather pouch back atop the bureau. He moved on to the length of plaid that Liam had draped across a chair, rubbed a corner of the fabric between his fingers, felt the weight of it. Griffin—who had never been given to the old ways—wore black pantaloons, a coat of dark brown superfine, and a pale gold waistcoat, striped in lovely shades of blue that reminded Liam of a flock of peacocks—particularly the fat overfed ones that roamed the gardens in and around the family estate, Talla Dileas.

“’Twas hand woven by the old widow MacDuff,” Liam informed him.

“Ah, of course it was, for who but the old lady MacDuff still makes them?” Griffin asked, and dropping the corner of plaid, turned his attention to Liam. He folded his arms across his chest, crossed one leg over the other, and glanced at his brother’s naked chest. “Tell me, did ye learn to sleep bare-arsed in the army?”

“No,” Liam said, pushing his legs over the side of the bed, “I learned to sleep bare-arsed in the ladies’ boudoirs.”

Griffin laughed, his grin as wide and as inviting as their sister Mared’s. With a yawn, Liam studied his younger brother. He was built like Liam—tall, muscular, dark brown hair, and eyes as green as heather—but he wasn’t quite as big as Liam, having more of the slender, aristocratic frame than the warrior physique for which Liam prided himself. And he was, admittedly, a very handsome man, whereas Liam was…well, plain.

Still laughing, Griffin moved toward the old plank wood door. “I’ll tell Douglas ye’ll join him yet,” he said. “And I’ll tell yer lady mother that ye have indeed promised to attend supper.” He stooped and ducked out of the cavernous tower chamber where the lairds of Lockhart had slept for decades until one had come along and added an entire manor to it.

Liam stood up, let the sheet slip from his naked body, stretched his arms high above his head, then moved to the narrow slit of a window that overlooked the old bailey.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)