- Home

- Julia London

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel Page 10

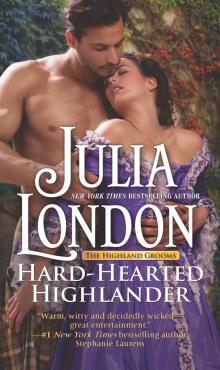

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel Read online

Page 10

After a lot of tossing and turning, an idea did occur to her. It wouldn’t be easy, but if Avaline cried off from her engagement—publicly, and for good reason—there was nothing her father could do. He would be angry with her, certainly—but he could not force her to marry Mackenzie if her grievance was made public—not legally, not morally. His power over his daughter existed in the privacy of this family’s affairs.

Convincing Avaline would be the hard part. She was an obedient and fearful young woman. But Bernadette was determined, if for no other reason than to best Lord Kent and his grand plans that so callously disregarded the well-being of his only child.

Or, perhaps it was far more personal than she was willing to admit, even to herself. The anger in Bernadette for what had happened to her still burned. Her father’s disregard for her feelings had been almost as painful as losing the baby she’d carried. Her father had said such vile things, had called her such horrible names, had said she was a whore, selling her body to any man who would pay.

Bernadette’s only crime had been to fall in love with the son of a shopkeeper. Unfortunately, that occupation was not what her father had in mind. Her father had become rich from making iron, and he saw Bernadette and her sister, Nan, as his entry into a higher level of society—not an inferior one. Bernadette’s crime was eloping with the man she wanted to spend her life with. And after they were caught and Albert disappeared, Bernadette’s ultimate crime had been discovering that she’d carried Albert’s child. Her bastard child, really, since her father had forced the annulment of her marriage.

The pregnancy did not soften her father’s heart; if anything it only gave him more reason to despise Bernadette. She’d been made a pariah, even among her own family, and then she’d lost the baby, and had almost lost her own life.

Her feelings has been disregarded, but Bernadette was determined that Avaline’s feelings would be heard and properly addressed.

The next morning, she walked into Avaline’s room without knocking. The girl was buried under a mound of coverlet and linens, and when Bernadette shook her leg, her head popped up from between a pair of pillows. She blinked the sleep away, then glared at Bernadette. “Go away. I don’t want to see anyone.” She fell facedown into the pillows.

“You’ve had an entire evening of self-pity, darling. Now is the time we must think what to do,” Bernadette said, and walked across the room to throw the windows open wide.

Avaline slowly pushed up. “Do?”

“Yes, do,” Bernadette said, and returned to the bed. “Your effort to be pleasing and courteous has not worked to garner any affection from...him,” she said. “Everything we’ve done thus far has only made you unhappy.”

“He makes me unhappy, and there is nothing to be done for it!” Avaline buried her face in the pillow again.

“Avaline,” Bernadette said. “Listen to me. You hate him, you said so yourself. There is nothing we’ve seen thus far that recommends him in any way, isn’t that so?”

Avaline snorted. “Nothing,” she agreed.

“So...if he is truly reprehensible to you, you might still cry off the engagement.”

Avaline slowly turned to look at Bernadette, her eyes filled with skepticism. “Father would never allow it—”

“Your father cannot legally force you into a marriage you don’t want...particularly if Mackenzie did something that everyone would see as unacceptable.”

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t really know,” Bernadette admitted. “But I think we should go to Balhaire today and call on him. The more time we are in his company, the better the chances are that he will do or say something so egregious, that no one can deny you have reason to end your engagement. There is a caveat, however—you must end it publicly.”

“Publicly,” Avaline repeated cautiously, and sat up. “But I thought perhaps I might make him a gift.”

Honestly, sometimes Bernadette wondered if the girl had been born without a full complement of brains. She drew a steadying breath so she would not shout her question and asked, “Why would you give him a gift, dearest? He’s done nothing to deserve it, has he? That makes no sense.”

“I don’t know,” Avaline said. “Perhaps I’ve gone about it wrong. Perhaps I’ve been too timid. You’ve told me more than once I’m too timid, Bernadette.”

Patience, Lord, please grant me patience. “But this is a bit different, isn’t it? I want us to find an opportunity that would give you reason to cry off. Do you see?”

Avaline shook her head. “I don’t see how I might.”

“Because I am confident—entirely confident—that we can discover something about him so objectionable that you would be well justified to end the engagement. But we can’t possibly know what that is if we avoid him. We must go to Balhaire and engage him.”

“I’ll take a gift, then,” Avaline said.

“Why?” Bernadette demanded again. “What possible good can come of it?”

Avaline shrugged.

Bernadette bit her tongue to keep herself from accusing Avaline of being the most cake-headed person she’d ever met. “What will you give him?” she asked skeptically.

“I don’t know,” Avaline admitted. “But I’ll think of something.” She drew her knees up to her chest and absently picked at a loose thread on the coverlet. “I would very much like to see Catriona again. I rather like her.”

“That’s no reason—”

“I’ve thought quite a lot about it, Bernadette,” Avaline said primly, interrupting her. “I’ve gone about it all wrong, I am certain of it. I want to try again.”

Well, then. Bernadette supposed she ought to be encouraged that Avaline had actually come to this conclusion all on her own, but she could only think she was woefully naive and impossible. “If that is your wish,” she said, forcing herself to sound as pleasant as she possibly could in spite of her great frustration.

“It is,” Avaline said.

“It won’t work,” Bernadette said, unable to help herself.

Avaline shrugged again. “Perhaps not. At least I will know I tried everything within my power to do as my father wished.”

That was the thing that made Bernadette groan. She sank down onto the edge of the bed. “What about what you wish, Avaline? What about you?”

Avaline gave her a tremulous smile. “Really, Bernadette, you know the answer to that. It doesn’t matter what I wish. It never has.” She stood up from the bed and walked to her bureau. She opened it, looked through the few things there and then held up a lace handkerchief to Bernadette. “I’ll embroider his initials on this.”

Bernadette looked at the delicate thing and imagined it in the hands of a brute. “It’s made of lace. He won’t care for it.”

“Perhaps not. But it’s the thought that counts, isn’t it?”

“In any situation but this,” Bernadette said bluntly.

Avaline looked at her curiously. “Why are you so cross?” she asked curiously. “You’ve always said a good woman’s first instincts should always lean toward compassion and kindness.”

The question set Bernadette back on her heels. She did always say things like that to Avaline. And for the first time since seeing the dark eyes of this particular Scot, Bernadette wondered why her instincts had leaned so far the other way. Oh, but it was obvious, wasn’t it? He was cold and cruel, and...and he was much like Bernadette’s father that was what.

Except that he wasn’t, really.

Today, she had sensed that Mackenzie’s was a different sort of darkness than her father’s.

“I’ll find some thread,” she said, and went out, mulling that over.

CHAPTER NINE

THEY FEEL AS if they are rebels, hiding away at Auchenard as they are, lying in bed, their legs laced with each other and in spite of

the bitter cold in a lodge with empty hearths, both of them slick with the sweat of having made wild love.

Seona twirls a bit of Rabbie’s hair around her finger, then traces a line down his chest. He catches her hand and kisses it, too spent to have another go. He wants to marry this lass, to make her his wife, to live at Arrandale and begin a family. But they won’t until her brothers return from Inverness, where they are part of the Jacobite army that has seized, and now hold, that stronghold.

“I donna want to wait any longer,” he tells her. “I want to wed you now, Seona. What we do here is immoral.”

She strokes his cheek and smiles sadly. “You know very well my father will no’ allow it before my brothers have returned, Rabbie Mackenzie.”

“Have you any word of them?” he asks, and kisses her breast.

“No. My father says Lord Cumberland is advancing, and they are needed to hold Inverness.” She shrugs and nuzzles his neck. “I donna want to speak of it now...do you?” She nibbles his ear.

Rabbie doesn’t want to speak of it, either, but he is filled with foreboding.

* * *

CAILEAN MACKENZIE, RABBIE’S oldest brother, was laird of Arrandale, the estate just up the loch from Balhaire. He’d built his house with his own hands. But as stately as it was, it was nearly uninhabited, save for its current resident, Rabbie, accompanied by the ghost of Seona’s memory, and Mr. and Mrs. Brock, an elderly couple who had survived the dispersal of the MacAulay clan. They had a cottage down on the shore of Lochcarron, only yards from Arrandale, and kept the house and grounds and animals and cooked for Rabbie when he was about. Their living was so quiet that Rabbie scarcely noticed them.

About a mile from Arrandale was Auchenard, the hunting lodge that Daisy—Lady Chatwick before she’d married Cailean—held in stead for her son, young Lord Chatwick. It sat empty now, as it had for many years. Since the rebellion had been put down, Daisy did not feel safe bringing her viscount son so far into the Scottish Highlands, fearing retribution for what had happened at the fields of Culloden. Someday, when Ellis was of age, he would come again. But for now, Rabbie saw after it. For the time being, they resided at Chatwick Hall in northern England, a grand place by the sound of it, where Ellis was being properly educated to be an English viscount.

Rabbie missed his brother and Daisy, he did, but the solitude at Arrandale suited him. He felt useless otherwise. He wasn’t even a help to his own father. Though his father’s leg bothered him very much, he was still the head of a clan, still had responsibilities to their extended family, although that family had been diminished. Rabbie couldn’t seem to summon the wherewithal to help his father in the ongoing affairs of Balhaire. Everything seemed so bloody pointless.

Catriona, whose future seemed as bleak to Rabbie as his own, had begun to handle more of their father’s dealings and, in notable contrast to Rabbie, without complaint. Her willingness to help where she could shamed him. They were born of the same parents, had shared the same upbringing. How could her heart stay as strong as it had, still beating, still capable of feeling, when his heart had turned so hard?

He thought of all this one day as he rattled around the estate, with nothing to occupy him but his thoughts. He was restless again, and decided to go to Balhaire. He found Mrs. Brock and told her not to leave supper for him. He also decided, as it was a fine, clear day, that he’d take one of the boats. It had been a very long time since he’d been on the water. One of the Balhaire dogs had followed him home two days ago, and eagerly leaped in the small boat and settled at the stern like a captain.

Rabbie pushed the boat away from the shore, then stepped in, found the oars and began to row.

The loch was still this afternoon, the rowing easy work. He glided past the point where they’d hanged Seona’s father, past the point the traitor Murray had led English soldiers to shore so that they could sneak inland to attack Killeaven and Marraig.

When Rabbie reached the place where the loch met the sea, the water turned a bit rougher. The rowing became work, and the dog came to its feet, as if on guard for any impediment in their path. Rabbie kept up his pace. His muscles burned to the point that he could scarcely feel his arms, but he did not let up. He wanted the burn to spread through every limb. He wanted to burn up completely.

He reached their cove without disintegrating into flames, however. The dog leaped from the boat, choosing to swim to shore. Perhaps it feared Rabbie would row it out to sea. He got out of the boat and sank into water above his knees. It was icy cold and filled his boots, and still, he didn’t care. If his body wouldn’t burn, perhaps it would freeze. He dragged the boat to shore and paused, looking up at the cliff. His cliff. It looked higher from here, which gave him a slight shiver. That might have been the result of the frigid water in his boots, but he couldn’t be certain.

With the boat secure, Rabbie began the half-mile walk from the shore to Balhaire, up a gradual slope, through a forest and then onto the high road, past shuttered houses and shops, past clan members who lifted their hands in half-hearted greetings.

When he reached the bailey, he realized something was happening. He was so accustomed to the bailey being empty now, but he could hear voices. And laughter.

He was met by a pair of dogs, who lifted their snouts to be petted. He obliged them for a moment, then ventured on and walked toward the sound of the voices. He went round the corner and found, to his surprise, his brother and sisters, and Vivienne’s children and husband, on the green. Fiona and Ualan were out as well, but standing apart from the others. Fiona was pulling grass from the green. Ualan watched the others intently.

But it was not the children that added to Rabbie’s great consternation. It was the presence of Miss Holly and Miss Kent. They were bowling.

Bowling.

He hadn’t seen anyone bowl on this green in years. He remembered when his father had brought them the kit from France, the balls polished to a high sheen, and he and his siblings had climbed over each other to touch them. For many years of his childhood, members of the Mackenzie clan would gather on the green on Saturday evenings, to dine and drink and play games such as this. Those times were long gone, and it made him sentimental to see his family at the sport now. His nieces and nephews were delighted; they were laughing and shrieking, running back and forth to examine each ball bowled.

It was strange to see Miss Holly and Miss Kent among them. Had he forgotten they were calling at Balhaire? He couldn’t remember any mention of it. He watched them for a moment, unnoticed. His fiancée was laughing at something Aulay had said, and pretended to collapse with laughter into his shoulder. Aulay, laughing, too, caught her and righted her, then let her go with a smile.

It was Miss Holly’s turn to bowl. She enlisted the help of several of the children to instruct her, then bent down in something of a curtsy, and rolled her ball. It wobbled down the path she’d sent it and knocked a blue cone out of its way. That was met by cheering from the rest of them, his nieces and nephews jumping wildly about.

He hesitantly walked toward them.

Fiona MacLeod was the first to see him. She waved, as if they were dear old friends. She began to skip toward him. Her brother didn’t move, but his gaze locked on Rabbie’s. That lad seemed to carry an invisible weight on his shoulders.

“Rabbie!” Vivienne said, noticing Fiona skipping in his direction. Suddenly, his nieces and nephews began to shout “Uncle Rabbie!” and soon, they had raced ahead of Fiona to throw their arms around his legs, laughing.

Fiona stopped, watching the other children with curiosity.

“Look at the lot of you, aye?” Rabbie said as he tousled the hair of several of them, then gestured for Fiona to join in the fray. She didn’t move. “Bowlers now, are you?”

“Uncle Rabbie, will you play?” asked his oldest niece, Maira. She had big blue eyes, like his Auntie Zelda.

�

�He’ll no’ play,” said Bruce. The lad was old enough to remember a boisterous uncle who would carry him on his shoulders and toss him in the loch on hot summer days. Rabbie remembered that uncle, too—he’d been lost somewhere along the way. He stroked Maira’s cheek and managed the best smile he could.

“Maira, leannan, he canna join the play in the middle of the game,” Vivienne said, and put her hands on her daughter’s shoulders. “Go now, it’s your turn.”

As Maira scampered back to the green, the other children, remembering the game, ran after her. Fiona had turned back, too, and was once again at her brother’s side. Vivienne rose up and kissed Rabbie’s cheek.

“What is this, then?” he asked, lazily returning her kiss.

“What do you think, lad? A game.”

“Aye, a game we’ve no’ played in years.”

“We’ve naugh’ else to entertain your fiancée, do we?”

He looked at Miss Kent. It didn’t appear she’d noticed him...but her saucy maid had. She was wearing a pale blue gown, and for once, her hair was put up properly, so that he had a complete view of her long, slender neck. She was also smiling, as he had rarely seen her do, and it was...charming.

Rabbie looked away from the smile to the MacLeod children again. “Why do they no’ play?” he asked, motioning with his head in their direction.

“I donna know,” Vivienne said thoughtfully. “It’s the lad, really—he’s a wee bit shy.”

“What’s to become of them, then?” Rabbie asked.

Vivienne did not look at him. She turned her attention to the green and said, “We are endeavoring to find a relative or a family friend who might take them in.”

She knew as well as Rabbie did that there was no relative to be found.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)