- Home

- Julia London

Highlander in Love Page 12

Highlander in Love Read online

Page 12

She gasped with surprise and smiled so broadly that it dimpled her cheeks. “’Tis a miracle! At long last we might agree on something, aye?”

But Payton did not respond. He was captivated by her green eyes, the sparkle that he’d wanted to destroy, the eyes that had moved him as he’d lain with Finella.

“’Tis rather odd, sir, how ye go about handing over yer clothing for laundering.”

There was something about that brash smile of hers that sent a tiny bolt of desire to his groin, and Payton once again felt like a monumental fool. He’d meant to punish her, to make her feel the indignant pain she’d heaped on him. But it seemed he was the only one to be humiliated, the only one to think of the kiss they’d shared that day high in the hills that had lingered with him for so long afterward.

Aye, he was a bloody fool, for he continued heedlessly to touch her ear and her neck with his free hand. Her cheeks filled with a blush, and she instantly dipped her head away from his hand.

Payton dropped his hand from her neck, yet he still held the other one tightly in his. “Ach, Mared,” he said quietly, letting go any pretense. “Ye’ve tormented me since we were bairns, aye?”

She snorted lightly. “I believe it was ye who tormented me, milord.”

“’Tis obvious I have tormented ye somehow, in some way, for ye’ve made it quite clear ye’d no’ have me, were I the last man in Scotland.”

“I never said so!” she protested with a tiny tilt of her chin. “If ye were the last man in Scotland, I’d have cause to reconsider…even if ye were a Douglas.”

He chuckled softly and shifted his gaze to the ripe lips he desperately wanted to kiss, feeling strongly now the powerful current of desire that had been so blatantly lacking earlier. “Reconsider now, leannan,” he said softly. “Think of the pleasures we might explore together under this roof.”

Her lips parted slightly; he could see the leap of her pulse in the base of her throat.

“Let go the past,” he urged her, lifting her hand and tenderly kissing the back of it. “Donna put yerself through this.”

Her eyes suddenly flashed with an angry glint. “It wasna I who put me here!” she sharply reminded him, yanking her hand free of his. “It is ye who put me here, with no more thought than if ye’d penned one of yer sheep!”

Her rebuke annoyed him—he abruptly turned away from Mared, shoved both hands through his hair and roared to the ceiling, “Diah, but ye bloody well vex me!”

“The feeling is entirely mutual, so I would suggest that as ye are no’ the last man in Scotland, ye give me leave to tend yer blasted clothing!”

“Aye, go, get out,” he said sternly, waving a hand at the door. “I’d just as soon no’ lay eyes on ye!”

“I’ll bloody well go,” Mared snapped and grabbed the tail of his neckcloth and yanked it hard from around his neck before whirling around and striding to the door.

“Hold there!” he bellowed. “Ye will take yer leave of me properly! I’ve warned ye, Miss Lockhart, I willna abide yer insolence in this house!”

She grabbed the door handle and yanked it open. “I will do the best I can to satisfy my family’s debt, sir, but if ye donna care for my service, then by all means, as laird and master of this house, ye should dismiss me from yer employ at once!” And with that, she stormed through his door without bothering to close it, so he could hear her marching down the corridor, away from him.

“Bloody rotten hell,” Payton muttered and glared at the fire. But when he heard her on the stairs, running down, running away from him, he swiped up his port glass and hurled it with all his might at the hearth and watched it shatter into a thousand little pieces.

It was ironic, he thought, infuriated, that he should feel exactly like that goddam port glass. Somehow, that wretched woman could, with a single word, shatter him into a thousand pieces.

Twelve

M ared wasn’t entirely certain why she didn’t send Una to his chambers the next morning, but she didn’t. She went herself and was, astonishingly, a wee bit disappointed to find he’d already gone.

But he’d made sure to leave behind quite a mess for her—his bed was in furious disarray, as if he’d thrashed about all night, and his toiletries scattered about as if he’d intentionally meant to annoy her. If that was his intention, he had succeeded.

Mared picked up a pillow and held it to her face. There was no smell of perfume there, as she had perhaps feared…just the darkly musky scent of Payton that floated down her spine to rest somewhere deep inside her.

His sleep had been as restless as hers, apparently—she’d had trouble ignoring the poignant look in her mind’s eye of his handsome face when he’d held her hand last night. It had struck her oddly—his gray eyes had shone dully with fatigue and desire, but there had been something else in them, too, something that warmed her and exhausted her all at once.

Aye, he exhausted her! One moment she was certain what she felt for him—he was her employer, so firmly in control of her life that she despised him, a Douglas who was to be endured rather than admired. But in the next moment, she saw a man, an incongruently vulnerable man with a hard masculine exterior who wore his heart on his sleeve. And she was not, she was discovering, above being charmed by it, if only for a moment. Several moments, perhaps. All right then, even a lifetime of moments.

The very thought that she might feel anything for him at all angered her. She tossed the pillow aside and carelessly made the bed, then turned her attention to the rest of the room, determined to be done with it. His clothes were scattered about, his toiletries left all over the basin. And there were the curious shards of glass around the hearth.

Just like a Douglas to have no care for expensive possessions, she thought, and carelessly kicked the glass into the fire pit. Then she shoved his toiletries haphazardly into the mahogany box and nudged his nightshirt under the bed. When she’d finished, she made her way downstairs to hand his laundry over to someone who would launder it.

She did not find a washerwoman. But she found Beckwith, whose pained expression seemed to brighten considerably when he told her that Eilean Ros did not employ the services of a washerwoman, as it was just the laird and a few staff living there, and that the last housekeeper had done the laundering every Thursday. Without fail. Or complaint.

“Surely ye jest, Mr. Beckwith,” she said, smiling hopefully. “I’ve no’ laundered as much as a rag before now.”

“Miss Lockhart, why in heaven’s name should I jest?” he asked, and it occurred to Mared that he couldn’t possibly even if he tried. “Follow me, and I will direct ye to the washhouse.”

“But…but I canna carry all of this!” she protested, gesturing petulantly at the mounds of linens and clothing that had been piled in the linen closet, waiting to be laundered.

“I’ll have Charlie bring it round. Rodina will come after ye’ve finished the laundering and bluing and help with the ironing,” he said and proceeded to the kitchen, calling over his shoulder, “Step lively, Miss Lockhart!”

She had a notion to step so lively that he might feel her boot in his backside, and hurried to catch up. Beckwith marched through the kitchen, nodding curtly to Mrs. Mackerell and Moreen as he went by. “I’ll no’ have her using me good pots, Mr. Beckwith!” Mrs. Mackerell shouted as they passed through.

Beckwith ignored her and continued on, through the kitchen washroom and out the small door onto the lawn. Not once did he look back to see if Mared followed him, but marched like a man on a mad mission.

Down the lawn he went, through a rose garden, through tall, wrought-iron gates, then turning on a small path and finally arriving at a washhouse outside the gate, all alone in a space between the house and the sheep. It was a small, square stone building with a weathered wooden door. Beckwith flung open the door and disappeared inside.

Mared followed him. There was a hearth with a large black kettle hanging over it. Three wooden tubs were along one wall, and leaning up against the wall between

them was what looked like a boat’s oar. On the opposite wall was a large contraption with rollers of some sort. There were two windows on two walls, the only available light. It looked, she thought, like a dungeon.

“Here ye are,” Mr. Beckwith said. “I believe everything is in order. Ye may draw water from the rain barrel on the south side of the washhouse.” And then he turned as if he meant to leave.

“Mr. Beckwith!” Mared cried, stepping to block the single door. “I’ve no notion how to launder! I know only that there’s a bit of tallow soap involved, and some boiling of water—”

“There ye have it,” he said, and moved to step around her.

“B-but…I donna know the order of things or how much tallow is to be used. Am I to blue the clothing? How shall I blue? I’ve never done such a thing!”

“Miss Lockhart, I trust ye will find yer way,” he said irritably. “’Tis no’ a mathematical equation. Please step aside. I shall send Charlie with the laundry,” he said and stepped around her and stooped to go out the small door.

She gaped at his departing back. She’d never done laundry—Fiona, Dudley’s wife, had always done the Lockhart washing, even after all the chambermaids had gone. And while Beckwith was correct in that the wash was not exactly a science, it did require a bit of instruction, did it not? Douglas, damn him! Why wouldn’t he employ the services of a washerwoman as did most lairds in Scotland? It was little wonder he had such wealth, so bloody frugal as he was.

She’d managed to fill the big kettle with water by the time Charlie brought the laundry down. She begged him for help, but Charlie laughed. “I’ve no’ blued a bloody thing in me life,” he said good-naturedly. “And I donna intend to start now, lass. Besides, the laird is receiving guests, and I’m wanted on the drive.”

“Aye, thank ye for yer help!” she called after him as he jogged up the path, and received nothing more than a shout of laughter for it.

When the water reached a boil, Mared siphoned some off and poured it in the first tub. She determined she’d start with something rather small to better gauge the amount of tallow soap needed as well as the amount of bluing agent. She dug through the pile of linens and clothing and picked out a handful of neckcloths. She shoved the neckcloths into the first tub, took a cake of tallow soap, and grimacing at the greasy feel of it, she put it in the water and watched it melt. Then she took the paddle, stuck it in the wooden tub, and began to swirl it around.

After a quarter of an hour, she had developed the start of a blister on one hand and determined it was enough swishing around. She put more water in the second tub, then lifted the dozen or so neckcloths from the first and put them in the second to rinse them of the tallow. That took some effort, as the tallow, made from sheep’s fat, clung to the neckcloths.

When she’d had enough of the rinsing, she put the neckcloths in the last tub and took the bluing agent from the single shelf in the washhouse and dumped some in. She was standing over the wooden tub, trying to determine if she should stir it or not, when Jamie sauntered in, his hands clasped behind his back.

“Look at ye, then, Miss Lockhart, so very industrious,” he observed as he glanced around the washroom. “Ach, put down yer paddle and come to the gardens with me. ’Tis a bonny day.”

“A bonny day?” Mared laughed. “It is gray and cool, sir, did ye no’ remark it when ye came from the house?”

“Aye, but when a lass is in me presence, on me honor the clouds lift and the sun shines.”

She laughed. “Rather poetic, sir, but I donna think the clouds will lift today.”

“No? Then cast a spell.”

Her hackles rose instantly. Jamie was no longer smiling, but watching her carefully. He made her quite anxious, and she instinctively reached for the paddle. “Would that I could,” she said, smiling thinly.

He suddenly dropped one hand that he held behind his back and held out a note to her.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“The laird has sent ye a note. A love letter by the look of it.”

Mared blinked. Her heart, her perfidious, miserable heart, skipped a beat.

“Aha!” Jamie exclaimed. “Ye hope that it is, I can see it in yer eyes.”

“That’s ridiculous!” she said, blushing furiously. “I fear it is more labor that he requires of me.” She reached for the note.

But Jamie jerked it out of her reach and waved it above her head. “What favor should I ask for yer love letter, then? Ah—I’ve a hankering to kiss an accursed lass. Ye’ll have yer love letter in exchange for a kiss.”

“Jamie!” she cried, trying to laugh. “Have a care! If Beckwith catches ye here, he’d dismiss ye straightaway.”

“Beckwith will no’ come to the washhouse, no’ when there are guests in the salon.” He held up the letter. “Come on, then, leannan. Give us a kiss.”

“Give it over,” she quietly demanded.

Jamie laughed nastily and walked closer, the letter held high over his head. “Kiss me now and I’ll give it to ye.”

She glowered at him, reached above his head for the note, but Jamie chuckled and jerked it out of her reach again and cocked his head to one side. “Well, then?”

Bastard. She felt very vulnerable and frantically thought what to do, her eyes darting to the door behind him, then to him again. Suddenly she smiled. “All right, then, lad. Come here, and I’ll give ye a kiss,” she said sweetly.

Jamie’s eye narrowed, and he grinned lecherously. He stepped forward, but as he reached for her, Mared swung the paddle out of the bluing tub and whacked him soundly in the ribs.

“Aaiie,” he bellowed and grabbed his side, dropping the letter in his haste. “Ye bloody wench! I was just having a wee bit of sport, ’tis all!”

“Take yer sport from someone else,” she said and stepped forward, waving the paddle before him.

“Bloody wench,” he muttered again, and still holding his side, he pivoted about and stooped to quit the washroom.

Mared waited until she was quite certain he was gone, and still holding the paddle, she retrieved Payton’s note.

M. Lockhart

It was the only mark on the outside of the note. Mared shoved the paddle into the bluing tub and broke the Douglas seal at the bottom of the letter as she moved to the window for light.

I have received your inquiry and would suggest that if you have such luxury in your day to pen long notes informing me what you will and will not do whilst in my employ, then perhaps you have too much time on your hands altogether. You might put your mind to more productive tasks. In that regard, my cousin Sarah brought it to my attention that the needlework on some four fire screens in the green salon and main drawing room are in need of repair. I suggest you put your hands to the better use of repairing those screens than the wasting of my ink and paper.

You have my permission to close some rooms in the north wing, as approved by Mr. Beckwith.

Douglas

That was it, the sum of his blasted note, and Mared was enormously disappointed, but moreover, quite miffed. She balled the note up and tossed it beneath the kettle at the hearth, and with arms folded across her midriff, she watched it curl up and turn to ash.

“That’s what I think of yer sodding note,” she muttered and turned sharply about…and saw the bluing tub. “Oh no,” she said. “Oh dear.” She had forgotten all about the bloody neckcloths. Using the paddle, she lifted the first one out of the tub. Her eyes went round when she saw it and with a squeal she dropped the paddle into the water and covered her mouth with her hand.

The neckcloth wasn’t the snowy white it should have been. It wasn’t even tinged blue. It was purple.

Mared suddenly burst out laughing. She laughed so hard that she bent over with it. When she at last caught her breath and had wiped the tears from beneath her eyes, she fished them all out to dry.

Payton enjoyed a successful meeting with Mr. Bowles from Stirling, a man who was keenly interested in investing in Payton’s distillery, an

d who was, incidentally, already exporting fine Scotch whiskey to England and France. And making a tidy profit from it, apparently.

At the conclusion of their meeting, Payton suggested they walk down to the loch so that Mr. Bowles might see for himself the crystal-clear spring waters that came down from the hills. As they walked outside, Cailean, Payton’s dog, came racing around the corner to meet them. He had, Payton noticed, a collar of some sort around his neck. And as they walked on, Cailean trotting ahead of them to the loch, Payton thought he must be seeing things, for he would swear it was a purple neckcloth tied around the dog’s neck.

When they reached the edge of the water, Mr. Bowles squatted down and put his hand in the loch, and Cailean put his snout at the man’s face. “Ho, there!” Mr. Bowles said, and reached for Cailean’s ear, scratching him for a moment before rising to his feet. “Good water is the key to good whiskey,” he said.

“Aye,” Payton agreed.

“If I may—is that a cravat about yer dog’s neck, milord?”

“Ah…” Payton paused, leaned down and had a look at the handsomely tied bow. “I believe it is,” he said, and mystified, he gave Mr. Bowles a small smile and a shrug.

They talked a little more about the water and walked a little farther around the loch, where one of the highland streams fed into it. When they started back, they passed a pasture where the milk cows grazed. “Idyllic place ye have here, milord,” Mr. Bowles said as they walked along the split-rail fence.

“Thank ye.”

Mr. Bowles suddenly stopped walking and leaned forward, squinting at the cows.

Payton followed his gaze. And he squinted, too. What in the bloody hell?

“Curious habit, using cravats as collars,” Mr. Bowles opined.

“Frankly, I wasn’t aware that we’d begun the practice,” Payton responded dryly.

Mr. Bowles chuckled. “I’d wager someone is having a bit of fun at yer expense, milord.”

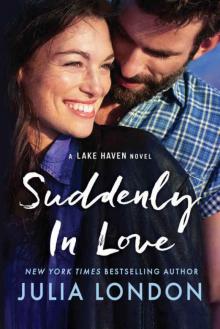

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)