- Home

- Julia London

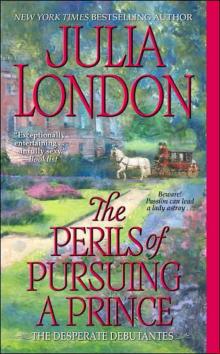

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Page 13

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Read online

Page 13

“Mrs. Bowen informs me that you would like to write,” he said.

“I…yes. Yes, if that is not too much to ask.”

He took another sip of wine, then pushed the goblet away. “Perhaps you would like to write in the conservatory. It is built into the gardens.”

“The conservatory?” she asked, her brow wrinkling.

“Have you not discovered it during your examination of this empty house?” he asked as he rose from his seat. A footman darted to his chair, moving it out of his way. The prince hardly seemed to notice him at all as he began walking toward Greer. “And I thought you’d left no stone unturned.”

“I have indeed,” she said jauntily. “I have endeavored to draw out my exploration of the castle as long as I possibly can in order to avoid having nothing to do.”

He laughed. Laughed. And she saw again that rare but lovely, endearing smile.

He paused directly before her and clasped his hands behind his back. He was a good six inches taller than she, and much broader. His green gaze, framed with thick black lashes—which she had found so hard and cold—seemed quite blistering now. She could feel the trickle of warmth that had begun in her scalp begin to seep down her spine and spread to her limbs.

“A good plan, all in all. The longer you are occupied in snooping about the castle, the longer you are not causing any particular trouble to me. Shall I show you the conservatory?” he asked in that damnably low voice of his, and gestured to his left.

Greer nodded and walked beside him. Or marched, as it were.

Neither of them spoke as they strode purposefully down that long, wide corridor, yet Greer was acutely aware of his powerful presence beside her, exuding masculine energy that caught her up in its wake and dragged her along. He walked quickly, his gait sure and strong, and she had the sense that he was endeavoring to contain himself to keep from leaving her behind.

They rounded first one corner and then another. The silence that surrounded them began to feel suffocating—Why didn’t he speak? Did he truly find her reprehensible, did he distrust her so much?

At the end of the next corridor, the prince suddenly took hold of Greer’s elbow and turned her to the right, into a small, narrow passageway. At the end of it was a door. He opened it and gently prodded her through.

She gasped with delight as she walked into the conservatory, forgetting the awkward silence that had accompanied them here. The conservatory was built onto a castle wall so that at her back was a stone wall. But the remaining three walls were made of windows, framed in stone. The ceiling above her was a glass dome, so that she could see the gray rain clouds scudding across the sky and, all around, the gardens.

“Oh my,” she said as she walked deeper into the room. “This is beautiful.” She moved to the rain-streaked windows and peered out. Grinning with delight, she turned around to the prince, who was watching her with hooded eyes, his hands still clasped behind his back, his expression unreadable. “It is truly lovely, my lord.”

One dark brow rose above the other. “Not too cold? Or ‘unaccommodating’?”

With a sheepish smile, Greer shook her head. “Quite the contrary. With a few pieces of furniture—a writing desk, of course, and a divan, perhaps, this could very well be the most inviting room in the entire castle.”

“Then I shall have it readied so that you may write to your heart’s content.”

“That…that is very kind,” she said, surprised, and walked to one of the glass walls to look out. Through the condensation, she could see what she thought was a water well, and impulsively lifted the handle that held the windows latched, opening one. But a cold blast of damp wind hit her squarely in the face, and she immediately moved to close the window—but the window would not budge. She wrapped both hands around the edge of it and pulled hard, but it would not move.

Blast it all. She dropped her hands, looked over her shoulder, feeling ridiculous. “Ahem. It would seem the window is stuck.”

He sighed; she turned and tried again. But then she felt him at her back, felt that huge presence closing around her, his essence pushing her against the window. He reached around her and wrapped thick fingers around the edge of the window.

He may as well have put a torch to her back, she was so very conscious of him. She could feel the strength and heat from his body, could feel it thrumming in that narrow space between their bodies. Her entire being seemed to come alive with it; as if some beast inside her were raising its head and sniffing the hot air around her. She shivered with the delicious provocation and wrapped her arms around her body.

With a good yank, the prince pulled the window to and latched it shut. But he did not move his hand. It remained there, on the latch, his fingers gripping the handle, his arm outstretched by her head. He was standing so close that she could have leaned back against him if she so desired.

In a warm fog, Greer turned partially toward him and looked up. He was staring down at her with eyes as soft as moss, his gaze skating down her body to her bosom, and lower still, to where she held her arms wrapped around her middle, then slowly up again. “I will have the hearth lit,” he muttered.

She nodded, unable to speak, unable to stop her heart from racing or her skin from heating. She could not help but recall her first night at Llanmair, when he had handled the charm at her neck, when his fingers had skimmed across her skin, spurring the first storm in her.

Yet this was different. Even though he had not touched her, she felt his desire more acutely somehow. Perhaps because he was not full of drink. Perhaps because this time, he knew precisely what he was doing.

He let his gaze linger on her lips, through which Greer was trying to breathe. If he continued to look at her like that, if he remained silent and continued to gaze at her with those eyes, she thought she might very well explode. She could not allow that—she’d already let go of too much.

“Do you know,” she said breathlessly, her eyes on his lips, “I have been reading the book you lent me.” Greer had no idea what she was saying, but she was desperate to find her sanity, some solid ground.

He didn’t seem to hear her as his gaze drifted to her bosom again.

“I found the story of Owain Glyndwr most exciting.”

He said nothing; his eyes continued to hungrily roam her body.

“You have some connection to him, do you not?”

“I do,” he muttered, contemplating her mouth again.

“He was very inspiring. The story of his rebellion reminded me of a poem I once knew: ‘Beware of Wales, Christ Jesus must us keep… ’” Her voice trailed off, and she frowned slightly, unable to remember the words while he looked at her mouth like that.

“‘That it make not our child’s child to weep,’” he murmured silkily.

Those words nudged something deep inside Greer, something that played on the fringe of her memory, just beyond her reach. “You know it.”

He seemed to shift closer; she could feel his leg against her gown. “I know it well, as does any child of Wales. You were taught it along with your letters.”

Greer drew an unsteady breath and unconsciously lifted her chin, half expecting to be kissed, half fearing that he would and half fearing that he would not.

But he did not kiss her. He removed his hand from the window and idly touched a curl at her temple with the back of his hand. “I confess, Miss Fairchild, I cannot help but wonder if you have truly forgotten all you ever knew about Wales,” he said as his hand drifted to her collarbone, caressing it, “or if you were rather lazy in your task of extorting money from me by failing to learn those things that would best bolster your claim and have now resorted to seduction.”

She caught her breath—the sudden change in him threw her off balance. “I beg your pardon?”

“You heard me quite clearly, I think.”

“How dare you!” she cried, stepping to the side and away from him. “I do not seduce you! How can you not take me at my word? I have given you no cause to disbel

ieve what I say. I have not eloped with Mr. Percy as you suggested I would—”

“Only because I prevented it.”

Her cheeks flamed with shame at the memory of it. “You are mistaken. Whatever you might believe, I would not have eloped with Mr. Percy.”

“That is what you say. But you are naïve if you think I don’t know what you’re about in your sudden tenderness toward me.”

“It is not tenderness!” she protested.

“Lust?” he asked easily.

“You are a vile man,” she said low, and certainly, the tender feelings she was experiencing a moment ago evaporated. “Just as your claim to have helped Percy is what you say.”

He frowned, walked to the hearth, and kicked hard at the grate to dislodge a clump of ashes. “I am speaking the truth. One day, you will wake up from this ridiculous infatuation you hold for Mr. Percy and realize that I helped you.”

To think that just moments ago she had teetered on the brink of desiring him!

“The only thing I am guilty of,” she said, her voice trembling now, “is allowing myself to believe you are something more than a beast.” She swept past him and out of the conservatory, angry with herself.

She had lost her mind! Having been locked in this godforsaken castle had made her feeble and had compromised her good judgment! Well, it would not happen again. Oh no. If she had to confine herself to the rooms in which his wife had died, so be it—she would not put herself in a situation that would prompt her to feel any sort of tenderness for that beast again!

She turned the corner, striding furiously away and down another corridor she had not yet seen, one that looked to be a portrait gallery.

Her step slowed as she noticed a six-foot-high painting depicting a man who resembled the prince. He was dressed in the ancient Greek costume and riding a chariot. He looked ridiculous. Greer paused below it and looked up. It was his father or his grandfather, she thought, judging by the date engraved on the gold plate at the bottom of the frame. And the man in the portrait had the same slant to his eyes as the prince and Percy, the same unsmiling countenance as the prince.

She rolled her eyes, looked to her right—and saw a painting of a young girl, dressed in current fashion. She was standing beside a tree, a furry little dog at her feet.

Curiosity won out over her anger, and Greer moved to her right to admire the painting. The girl was a doe-eyed, golden-haired, timid little beauty, perhaps five years of age. Who was she? And why did the Prince of Thieves include her portrait in this gallery of thieves? One would think mothers would keep their daughters quite far from this place.

She started to walk again, but the portrait on the other side of the young girl stopped her cold.

She’d never be certain what caught her eye, but as she stood in front of the painting, something absolutely took her breath away. It was a portrait of a country picnic. There were several people gathered—a man with a violin, ladies on blankets, and children running with puppies. There was a man standing in the forefront who vaguely resembled the prince, and two young girls standing beside him, under a tree, one whispering to the other, who gazed out at the artist.

But most startling was the house in the distance. It was a grand white house, a mansion, surrounded by a lush lawn and grazing cattle.

It was the house from her dreams, the very house in the dream in which her mother had appeared. It was a house she vaguely remembered, but she was confused if she had actually been to it at one point in her life or merely believed that she had because she had dreamt of it so often.

How was it possible that a painting of that house was at Llanmair?

She stared at the painting, taking in every detail of it as she fingered the charm at her throat. It looked to be in a valley…in a valley! She had seen a white house in a valley just as the lightning had struck!

A noise at the far end of the gallery jerked her attention away, and a moment later, the prince strode into the gallery, halting at once when he saw her.

She felt as if she couldn’t breathe and could do nothing but point at the painting.

With a frown, he looked at the canvas. “What is it, Miss Fairchild?”

“That house—”

“Is closed,” he said instantly.

His response confused her. “What? But it can’t be! I saw it, in the valley just as the lightning hit!” she insisted.

His gaze turned hard. “What you saw is an empty shell. That house is closed.”

“No,” she said, shaking her head as she turned frantically to the painting. “I must see it. My—”

“Miss Fairchild, heed me. You are forbidden to go near that house. Do you quite understand me?”

“But I—”

“Miss Fairchild!” he snapped. “I don’t know what you might believe or have heard about that house, but it belongs to me, and I have forbidden you and everyone else in this county from going there! So if there is nothing else?”

She gaped at him. Then her eyes narrowed with ire. “No, my lord. There is certainly nothing else.” She turned away from him and strode from the portrait gallery.

When she had gone, Rhodrick looked at the painting and the portrait of the girl beside it and grimaced. He could never explain to Greer Fairchild, or anyone else for that matter, that the woman who came to him in his dreams, the woman he had believed Greer to be in his inebriation several nights ago, had led him to discover unspeakable tragedy in that house. As long as he lived, Kendrick would remain closed. He walked on, unwilling to think of it now.

Unable to think of anything but how dangerously close he’d come to kissing her.

Thirteen

W hen Ifan sought Rhodrick out with an urgent message from the groundskeeper, Rhodrick was grateful for the diversion. The retaining wall they had worked so hard to repair was failing, and it was precisely the sort of task he needed after that encounter with Greer Fairchild, the sort of task that would erase his voracious desire to kiss her, a desire to which he had come precariously close to succumbing. If he had, it would have made him an even bigger fool than he feared he was already.

Greer Fairchild did not want him. She wanted his money.

But standing next to her in the conservatory, with the torrid image of her nearing the throes of passion in Percy’s arms, he had almost done it, had almost given in to his baser male instincts.

He thought a bit of hard work would mend that deplorable lack of control, and that is how he came to be standing up to his knees in mud, his clothing soaked through, his shoulders aching from the swing of the sledgehammer he used to pound stone into place, wedging it between the others so the mortar could be applied.

It felt good, but it felt futile. The push of earth against the retaining wall was a far greater force than he was capable of containing. But it held for the time being.

When Rhodrick returned to the master suite and the hot bath Ifan had waiting for him, he felt himself again, fully in control of his emotions and his male instincts. It had been a momentary weakness, brought on by the sight of her ankle as she had gone up on her tiptoes to open the window. Or perhaps the shape of her derriere as she’d leaned over to see out the window. Or the brightness of her angry eyes in the portrait gallery.

Never mind—he felt so recovered, in fact, that he decreed if Miss Fairchild wished to be fed that evening, she would dine with him, for he saw no reason his staff should be burdened with serving two suppers at different times and locations.

“As you wish, milord,” Ifan said, but it was clear to Rhodrick that his longtime butler did not believe the serving of two suppers to be quite the problem that Rhodrick suddenly deemed it.

Nevertheless, he thought it wise to keep his eye on Miss Fairchild. He refused to acknowledge, even to himself, that he might actually enjoy her effervescent company. She was stubborn and far too sure of herself, and moreover, deceitful. He was merely protecting his property, nothing more.

Rhodrick dressed carefully, donning a waistcoat and suit

just delivered from his tailor in Aberystwyth. The tailor, who knew of his affliction with color, sent coats and waistcoats that were meant to be worn together. He knew that the coat and trousers of this new suit of clothing were black, and he thought that the striped waistcoat was a shade of green. Or red.

Whatever the color, it was well made.

He combed his hair back, and wondered about the style of it. He’d not been to London in years—he hadn’t the slightest notion of what was fashionable any longer. So he tied it in a queue with a ribbon, stood back, and looked at himself in the mirror.

He was tall, at least two inches over six feet. He was an active man, so he had not developed a paunch around his middle as so many of his peers had seemed to acquire in the last few years. No one could find fault with his form, he thought, but his face always gave him pause. He wasn’t hideous, not like a man he’d seen as a boy whose face had been eaten away by leprosy.

But he was not, by any definition, a handsome man. His sister was considered very handsome, as were his parents. He looked like none of them. His eyes were too close together, someone had once told him, and his nose crooked from having been broken more than once. The scar across his right cheek crossed the corner of his eye, the result of a fall from a horse that also had broken his arm and his leg, as well as his nose for the third time. The wound on his face had not healed properly, and though it had been years since the accident, it was still noticeable and quite ugly.

Rhodrick was angry with himself for caring. She was a thief. An attractive thief, but a thief nonetheless. Still, he studied himself critically, noting the crow’s-feet deeply embedded in the corners of his eyes, the constant shadow of his beard, and the gray that was beginning to appear in his hair.

His father used to say that he possessed a face that would frighten the ghosts from the attic. He used to tease him that he looked like Goliath depicted in the biblical painting that hung in the grand salon. When he and his sister, Nell, had come of age, the family decamped to London to immerse Nell in the social whirl of the Season. Rhodrick’s entry into society had been an afterthought, and his mean looks had prevented him from pursuing debutantes. His mother had tried to soothe him, saying more than once, “Someone will come along who cares not a whit for looks, my darling.”

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)