- Home

- Julia London

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin Page 13

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin Read online

Page 13

“Lily,” he said, his eyes blazing with desire. “Forget that now.”

Her craving for more was a shock of light through her. So many images and thoughts competed in her head. Desire burned in her, and she tried to focus, to think. Doubts about what she was doing, doubts about Aunt Althea, about Mr. Scott, and the events of that summer, began to crowd in between the overwhelming desire she was feeling.

She recalled the way her aunt had smiled at Mr. Scott, the way Tobin had smiled at her. She had a flash of memory of her aunt and Mr. Scott coming out of the potter’s shed one day, her aunt’s hair mussed, laughing. She’d told Lily she’d broken some pots. But the way Mr. Scott had looked at Aunt Althea had been the way Tobin had looked at her only moments ago—with ravenous, unapologetic desire.

Clarity hit Lily like the cold rain beginning to fall. She pushed at Tobin. “No!” she said, startled. “They sent us away!”

Tobin ignored her, but Lily’s lust was overcome by anger, and she shoved at Tobin again. He paused, lifted his head as if it took some effort, then brushed her wet hair from her cheek. Rain was falling steadily now.

“They sent us away, didn’t they?” she demanded of him. Tobin calmly returned her gaze. “Were they . . . were they lovers?” She was sure of it, but she needed Tobin to say it.

He did not seem surprised by her question; he obviously knew it to be true. Lily scrambled up out of his reach as the pieces of memory began to click into place.

Tobin bent down to pick up her cloak. “It is raining,” he said, and put the garment around her shoulders.

“Keira discovered it,” Lily said. “She told me, but I could not believe her. She showed me the stool your father made for the pianoforte.”

Tobin showed no emotion as he fastened her cloak.

“There is an inscription underneath,” Lily pressed. “One that was obviously inscribed for my aunt and was signed with the initials J. S. And I . . . I’ve been thinking, I’ve been trying to put together the pieces of mem—”

“I’ll get the horses.” He walked away.

“They were much closer than I understood them to be, but you understood it!” she called after him.

He paused between the horses. She saw the clench of his fist, the rise of his shoulders as he drew a deep breath. His reluctance to speak, his infuriating calm irked her.

“You are the only one who can tell me the truth now, Tobin. Do you think I haven’t wondered about it all my life? Do you think I haven’t lived with the thought that I am the one who saw him at Ashwood that night? I saw him riding away. I saw the lovers in the hall, too, but I did not realize it was them.”

“We should go,” he said flatly. He checked the cinch on his saddle, then hers.

Lily grabbed his arm, making him take a step back. “Did you know about the stool? It reads, ‘You are the song that plays on in my heart; for A, my love, my life, my heart’s only note. Yours for eternity.’”

“Foolish woman,” Tobin muttered. He put his hands on her waist to lift her into her saddle, but Lily pushed back. “I will not be dismissed! I did not know—how could I have known? I was only eight years old; I had no concept of such things.”

Tobin grabbed her and forcibly lifted her onto the saddle. “I cannot see the relevance of it now.” He slapped his crop against her horse, which started forward.

“It is entirely relevant now!” she argued, drawing her horse up. “If they were lovers, then why would he have stolen the jewels?”

Tobin suddenly whirled about, his eyes hard and cold. “How can you be so bloody obtuse, Lily? He did not steal them. Yes, God yes, they were lovers! If he was at Ashwood that night, it was for an assignation—not to steal her bloody jewels!”

Lily gasped. Tobin vaulted onto his horse. The rain was coming down much harder now, but she didn’t care. “But don’t you see? If he didn’t steal them, if they were lovers, we can exonerate—”

“The time to exonerate him was fifteen years ago!” Tobin shouted at her. “You are fifteen bloody years too late to exonerate my father, for he hanged at the end of a bloody rope on your word! He is dead—my father is dead, his name forever slandered, and to exonerate him now does naught.” He spurred his horse forward, galloping away.

The bitterness in his voice shook Lily. Her memories, so much clearer now, shook her. When Keira had told Lily, she had refused to believe it. But now . . . she wondered how her aunt had allowed her lover to hang?

Her chest felt constricted. She glanced up the road. She couldn’t see Tobin, and neither could she make herself move, paralyzed by the enormity of the truth and her part in it.

She recalled Althea’s mad search of the house after that night and realized now that she’d been searching for the jewels. She thought of her aunt’s strange death. An accident, they’d said, but Lily had always found it curious, since her aunt had been strong and had rowed that lake so many times. She saw all the events of that summer again, spinning out before her like acts in a play. “Tell the boy to see to her.”

She leapt off her horse and stumbled toward the cottage, recalling the many times she’d been sent away so she would not see her aunt’s adulterous affair, Tobin ordered along to watch over her. They had not been friends—he had been her keeper.

“For God’s sake,” he said. “Come here.”

She whirled around; Tobin had come back.

“I’m fine,” she insisted, but Tobin grabbed her and put her on his horse. He tethered her horse to his, then swung up behind her and pulled her into his chest. He spurred his horse and they moved along at a good clip.

Lily tried to resist sitting so close, but the rain was cold and hard, the wind even colder. She felt suddenly exhausted, her mind reeling, and she sank into his support and warmth. She needed it.

When they arrived at Ashwood, the storm was raging and the rain had turned to a stinging sleet. The door swung open, and the footman Preston raced down the steps, fighting with an umbrella, as a stable boy ran forward to take her horse. Tobin had Lily down before Preston could reach them.

She grabbed Tobin’s hand before he could pull away. “We could find them, Tobin.”

He ignored her, gesturing to the footman for the umbrella.

“We could find the jewels and then we could clear his name.”

Suddenly, nothing seemed more important. She had to do it. She could never change what had happened that summer, but she could at least find those jewels for Tobin.

But he looked at her disdainfully and pulled his hand free.

“Your ladyship, this way,” Preston urged her.

Lily ran with him into the house, where Linford was waiting to take her wet things. When she looked back, Tobin was gone.

TWELVE

Tobin had discarded his wet coat and waistcoat, and had pulled his shirt from his trousers. Carlson had tried in vain to direct him to a hot bath, but Tobin had stood aboard ship decks in far worse weather and did not require that sort of pampering.

What he required was a stiff drink.

He paced before the roaring hearth with a brandy snifter dangling between two fingers. He was conflicted, and he was not a man to be conflicted. He never cared enough about anything to be conflicted. And on those rare occasions he did care, as in the case of his father’s unjust death, his path was exceedingly clear—very black and white without even a hint of gray.

Yet for a few highly charged, highly pleasurable moments this afternoon, his path had not been so clear. The mud in him had disappeared, and in its place had come a vastly different feeling—he’d been an inferno, wanting the one woman he did not want to want. What he wanted was to ruin her—not to desire her. Not to feel enslaved to her body and her smile. But desire her, he had. Kissing her had breathed lifeblood into him, and he’d risen from the dead in those moments. The sensation had been an odd one—not the thickness in his throat, nor the tightness in his chest. But something even deeper, even more frightening than that.

Then it had all chan

ged again in the space of a single breath. Lily had had some sort of epiphany, and it had changed. Had she really not understood until today what had happened between her aunt and his father?

Tobin had suspected it as a lad, and he’d realized it had been true when, as a young man, he’d experienced his first infatuation. Besotted with a woman, he’d mulled over the ways he might express his adoration. He’d remembered his father’s stool then, the one he’d return to night after night when the family’s evening meal was done, painstakingly crafting its inscription. His father had often inscribed things in his work, but even at thirteen, Tobin had understood that one inscription to be different. It wasn’t until he was a man that he understood what that difference was.

Part of Tobin wanted to disdain Lily completely for suggesting, fifteen years too late, that she ought to find the goddamned jewels. Yet part of him wanted to find the bloody things for the very reason she suggested, to exonerate his father—and without her help, he’d have no hope of it. Wasn’t vindication a better path than revenge? That moral high road, the thing that a decent man would seek. Or did he owe his father and his brother and his mother an eye for their eyes, and Charity for her wretched life? Wasn’t a man who had failed to protect his family impelled to avenge their deaths?

Tobin tossed his brandy into the fire, watching it flare. He’d wanted his revenge for so long now that he scarcely knew how to think of it in any other way.

But his path to seeking it was becoming less clear to him.

The weather did not improve, and by week’s end, a lead gray sky had begun to spit a few anemic flakes across the West Sussex landscape. Mr. Joshua Howell, Tobin’s secretary, appeared at Tiber Park on a morning Tobin had chopped hedgerow. Tobin idly rubbed his forearm as Mr. Howell reviewed a tedious list of engagements, commitments, and correspondence needs. When they’d finished, Mr. Howell stood to go.

“One last thing,” Tobin said, his wet boots propped carelessly on the edge of the desk as he absently watched the bits of snow floating through the air. “I should like you to pen an invitation to Lady Ashwood to my winter ball.” He’d deliberately not invited Lily, for reasons that now made little sense. Now, he wanted her to see firsthand the influence he wielded here.

“Yes, my lord. Perhaps that will lift her spirits.”

Tobin shifted his gaze from the window to Howell. “What do you mean?”

“I have heard she is unwell, taken to her bed with an ague.” He picked up his satchel. “Seems she was caught out in the rain.”

Tobin’s heart skipped on a small twinge of guilt. “Pen the invitation. I’ll deliver it personally.”

“Yes, my lord,” Mr. Howell said and walked smartly out of the study, his satchel swinging at his side.

Tobin stood and walked to the window. He stared out at his holdings, recalling that sensual afternoon. Lily had been soaked to the bone. He put his hand to his abdomen. What was that he felt in his gut? Remorse? Highly unlikely. But he’d pay her a call all the same and assure himself that she would make a full recovery.

Tobin’s horse kicked up a powder of snow on the route to Ashwood. The snowfall was thickening. He would make a point of not staying more than a minute or two.

At the door, Lily’s butler eyed him with a perplexed look, as if he didn’t know whether or not Tobin was welcome. But as the snow was piling onto his shoulders, Tobin said, “If you would be so kind as to make up your mind.”

Linford stood back and bowed. “Please come in, my lord.”

Tobin strode into the foyer and looked at the magnificent dual curving staircase, his father’s masterpiece. The few times he’d seen it since returning to Hadley Green, he’d been astounded by the craftsmanship. Every baluster was handcrafted. The twin railings had been carved with an ornamental vine and leaves. He could recall little things, such as his father’s hands, the sound of his laughter. But he’d not recalled the depth of his talent until he saw this wonder of wood and physics.

“May I have your cloak?” Linford asked.

“That is not necessary,” Tobin said. “I do not intend to stay long.”

“I beg your pardon, my lord, but her ladyship has taken to her bed.”

“So I have heard,” Tobin said as he handed his hat to Linford. “Will you please inquire if she will receive me?”

Linford set Tobin’s hat on the console. “If you will kindly wait here,” he said and walked to the stairs. He moved slowly up, his hand on the railing, his steps deliberate.

Linford’s footfall had just faded into the corridor above when Tobin heard a giggle, the unmistakable sound of a child. He glanced up. He could see Lucy Taft crouched behind the balusters, spying down at him. It was exactly the spot where Lily used to hide to spy on the adults below. “I see you,” he said.

He heard Miss Taft’s soft gasp and saw her shift.

“That does not help you. And as we both know that I see you, I should think you’d come down here and tell me how your mistress fares.”

Miss Taft stood up, her blonde head peeking up over the railing. “She’s unwell,” she said and draped her arms over the railing. “She has an ague.”

“And what is your prognosis, Miss Taft? Will she make a complete recovery?”

The girl mulled that over as she kicked one foot in and out of the space between the balusters. “I believe she will,” she said with a sage nod. “But she must not go out in the snow, and she must eat all her soup. Mrs. Thorpe says that soup is the best thing a sick person might eat. Mrs. Thorpe does not care for beet soup. I have never tasted beet soup but I have tasted onion soup, and I don’t care for it. I like duck soup the best. What soup do you prefer, my lord?”

“Brandy.”

“There’s no such thing as brandy soup! Did you come to see the countess?”

“I did.”

“I can take you to her, if you’d like. I’m allowed to sit with her and read to her. But I don’t read very well, and she said that she thought five readings of ‘The Rabbit and the Hare’ were quite enough,” she said, and twirled around for emphasis before hopping across the landing like a hare. “You may come up if you like,” she said, just as Linford shuffled back into view.

He passed Miss Taft without a word, took the steps very carefully down to the foyer, and bowed before Tobin. “Her ladyship will receive you now.”

“I’ll take him!” Miss Taft shouted.

“I rather think I should, miss.”

“But I want to do it.”

Linford glanced heavenward. “As you wish.” He spoke in a manner that suggested this was not the first time they had vied for the introduction of a visitor. “If you please, my lord, Miss Taft will announce you,” he said, and gestured grandly to the girl at the top of the stairs.

Tobin started forward. This would be the first time he’d stepped foot on those stairs in fifteen years. He put his hand on the railing, felt the deep groove of the meandering vine and the leaves of various shapes and sizes. The staircase was remarkable.

“We are to be quiet as mouses,” Lucy whispered loudly when he reached the landing. “Mrs. Thorpe says her ladyship cannot rest if you run up and down the corridor.”

“I have no intention of running up and down the corridor.”

“Then you must have a very good mother,” Miss Taft said as she began to hop down the corridor before him. “Mrs. Thorpe says I am as wild as a monkey because I have no mother, and mothers make certain that proper young ladies do not swing from the house chandeliers like monkeys. Did your mother tell you that?” She paused to look curiously at him.

“My mother is not alive.”

“Are you an orphan?” she asked excitedly. “I am an orphan. The countess is an orphan, as well, although she had an aunt who very much wanted to be her mother. I think I might have a father, but I don’t remember if I do or not. Do you have a father?”

Tobin shook his head.

“Count Eberlin!” she said sternly, and slipped her hand into his damp palm wit

hout invitation. “I should think someone might have told you that you are an orphan. You are, you know, if you have neither mother nor father, and someone else must take you in and feed you and teach you proper keticut—”

“Etiquette,” he said.

“Etiquette, then you are an orphan.”

“Thank you for the clarification.”

“You are welcome,” she said, and let go his hand and skipped ahead to a door. She grabbed the handle with both hands and pushed the door open, then skipped inside. “I brought that wretched Count Eberlin to see you,” she announced loudly.

“Lucy!” Lily croaked.

Tobin strode into her bedchamber behind Miss Taft. “That wretched count at your service, madam,” he said, and bowed low.

“I beg your pardon,” Lily said and smiled apologetically as Lucy rushed across the room and plopped down on a window seat. “I am very surprised to see you, sir.”

Generally, Tobin had no compunction about entering a woman’s boudoir, but on this occasion, he felt awkward. The room was done up in soft pinks and crème-colored walls, not unlike the private rooms he had enjoyed in Europe. But the paint was peeling and the carpets were worn. It appeared as if it had once been a grand estate, where the money had gone before the house.

As for the room’s mistress, Tobin was quite taken aback by how pale and drawn she looked, save the rosy spots of fever in her cheeks.

Miss Taft suddenly gasped. She climbed up onto her knees on the window seat and leaned forward into the deep window well, pressing her hands against the panes of glass. “It’s snowing! May I go out, mu’um? Please?” she asked, whirling around and bouncing off the window seat.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

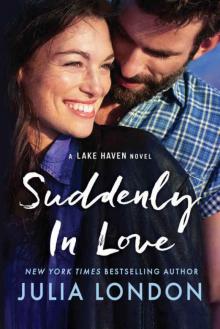

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)