- Home

- Julia London

A Light at Winter’s End Page 3

A Light at Winter’s End Read online

Page 3

Holly made her way up the stairs with the worn red carpet runner and down the hall to the nursery.

The shades had been pulled and it took a moment for Holly’s eyes to adjust to the darkened room. The walls were still covered in the faded yellow wallpaper with the green ivy vines, and it had begun to curl away from the wall in one corner. The old braided rug was the same as it had been when Holly and Hannah were girls, but there was a crib in here now, and a changing table, and a rocker in one corner of the room that looked as if it had been picked up from a garage sale. There was also a portable Baby Einstein Play Gym.

Mason was sitting in the middle of his crib like a Buddha, his fists on his dimply thighs. He watched Holly with big blue eyes, and as Holly drew closer, he suddenly gave her a big toothless grin and gurgled.

Holly grinned and dipped under the elaborate mobile with the airplanes and helicopters and picked him up. “Hey, Mason,” she whispered. She loved the almost weightless feel of Mason in her arms. She loved the smell of baby lotion and the smooth, silken feel of his skin. She eased down on the floor with him and laid him on his belly in his play gym, and watched him chew on the tail of the dolphin.

She could watch him for days, Holly mused. There was something endlessly fascinating about babies, and in a corner of her heart it made Holly wish for her own. That wasn’t something she knew how to pull off with her lifestyle and income, or any practical knowledge for that matter. Not to mention a lack of a sperm donor. But she was thirty-four years old, and there were times—like now—that she ached for a Mason.

She picked him up under his arms and had him stand in her lap. He began to gurgle and bounce on his fat little legs, up and down, up and down, as he reached for her nose and her earrings. He’d managed to get the little silver peace sign she wore on a chain around her neck into his mouth when Hannah walked in with his bottle and a blue plastic cup.

“There he is,” she cooed, and put the bottle aside to hold out her arms for her baby. Holly handed Mason up to her, then got to her feet.

Hannah kissed Mason’s round head. She put one hand to his bottom and frowned. “Didn’t you change him?”

It hadn’t even occurred to Holly. “No, I—”

“Babies are generally wet when they wake up from a nap,” Hannah said. She put Mason on the changing table. “My little man,” she cooed as she changed him. “Did you have a good nap? Are you hungry?” When she had him in a fresh diaper, she picked him up and lifted him up over her head, giving him a playful shake. Mason kicked his legs and stuffed a fist into his mouth. “I love you, baby boy,” Hannah said, and kissed his face before settling him on her hip.

“He’s growing so fast,” Holly said.

“And he’s got the appetite of a horse,” Hannah agreed.

“What does he like?” Holly asked.

“Huh?’

“To eat,” she clarified.

Hannah looked blank. “To eat?”

“You were saying—”

“The usual baby food stuff,” Hannah said with a shrug, interrupting Holly. “There is nothing this kid won’t eat. Isn’t that right, sweet pea?” she asked, tweaking Mason’s nose. Mason grasped his mother’s finger and tried to put it in his mouth. “People are starting to leave,” Hannah added without looking away from Mason. She was swaying now, side to side, bouncing him a little.

“Oh. Okay,” Holly said. “I’ll go and thank them for coming.”

“If you wouldn’t mind.”

Holly leaned over to kiss Mason’s cheek, but when she did, she thought she smelled alcohol and looked at her sister curiously. “Have you been drinking?”

“Yes,” Hannah said. “It’s been a trying day.”

It had certainly been that. “Yes, it has been trying,” Holly agreed. “Okay, Mase, here’s your aunt Holly, going out to thank everyone for coming,” she said, and started toward the door. She paused there and looked back at her sister. Hannah’s focus was entirely on Mason; she was speaking softly to him, chattering in the language of mothers. “Hannah.”

Hannah looked up.

“Thanks for taking care of everything,” Holly said, gesturing vaguely in the direction of downstairs. “The funeral, I mean. You did a really great job, and I know it’s been hard with your job and Mason and everything else.”

Hannah didn’t say anything—just stood there, staring back at Holly as Mason mouthed her shoulder.

Holly expected her to at least say No problem. Or even Thanks for noticing. Something. Why didn’t she speak? “Okay,” Holly said. “I just wanted to say thanks.” Bewildered, she turned back to the door.

“It was hard,” Hannah said, her voice low. “Harder than you can possibly know.”

Holly looked back at her sister. She could see the stress and wondered if maybe, Hannah was actually opening up to her.

“I spent every waking hour making sure Mom had what she needed,” Hannah said, and suddenly swiped up the bottle from the dresser. “I haven’t had a moment to myself since she got sick.”

There was an accusatory edge in her tone, and Holly steeled herself. “I know. You’ve gone above and beyond.”

“Then maybe you can appreciate,” Hannah said as she maneuvered Mason into her arms and handed him the bottle, which Mason eagerly took, “how hurt I was when Mom left it all to you.”

Holly had already started nodding, but suddenly stopped. “Wait … What?”

Hannah’s gaze was hard, her jaw tight. “You heard me.”

“Yeah, I heard you, but that’s crazy,” Holly said. “What are you saying?”

“Don’t pretend you don’t know—”

“I have no idea what you are talking about!”

Hannah tossed back her head with a groan. “Come on, Holly! Are you going to tell me that you didn’t talk to Mom about it in the last couple of months?”

Holly’s head was spinning. “Talk to her about what?”

“About her will!”

“Her will? Are you kidding?” Holly tried to recall if she and her mother had ever discussed her will, other than to note that her mother at least had one. “It never occurred to me, Hannah. She said she had one, and I left it at that. I just assumed that everything would pass to us.”

“Really?” Hannah asked skeptically. “You never wondered what Mom was going to do with the homestead? What her final wishes might have been? Do you honestly expect me to believe that?”

“I don’t like the accusation in your tone,” Holly said, folding her arms. “You’ve obviously thought about it. You’ve obviously read it, and Mom is hardly even buried. So if you have something to say, Sis, just say it.”

“Mom left the homestead and all her savings to you.”

Holly was stunned. “There is obviously some mistake. I don’t know where you got that idea, but I am sure it is easily cleared up, because it is not true.”

But Hannah was already shaking her head. “There’s no mistake.” Mason pushed the bottle away, but Hannah pushed it right back in his mouth. “She left it all to you, Holly. And I have a hard time believing you didn’t know it.”

Holly couldn’t make sense of it. It was inconceivable—her mother had thought Hannah was the greatest daughter in the history of the world. “You’ve got something wrong, Hannah. She left it to both of us.”

Hannah snorted and turned away. “Read the letter yourself.”

“What letter?” Holly demanded heavenward.

“The one she left with her pastor, along with a copy of a will that I have never seen. The one where she writes that she left it all to you, to poor, helpless, hapless Holly, because you would need it worse than me, because you didn’t have anyone to take care of you and you couldn’t make your way in the big bad world.”

That stung. Even in death, Holly’s mother had found a way to criticize her. “If that is true—and I don’t believe it is, but for the sake of argument, if it is—I’ll give you half of everything, Hannah. I mean … is there anything besides this house

? Whatever it is, I will give you half—”

“God, that is so like you to completely miss the point,” Hannah said coldly, and put Mason in his crib with the bottle. Only Mason didn’t want in his crib. He started to cry. Hannah swiped the cup of the dresser and drank deeply.

“What point am I missing?” Holly demanded. “You are practically accusing me of stealing this run-down old house! I had no idea Mom did that—This is the first I’m hearing it, and I’m telling you, we will share—”

“It’s not the estate!” Hannah cried, and Mason wailed. “The point is that while you were here in Austin, slinging frozen coffee drinks and writing your songs,” she said, flittering her fingers at Holly, “I was working fifty hours a week, taking care of Mason and Loren and Mom. Just like always! I took care of everything while you were off doing whatever it is you do, and she rewards you?”

Holly recoiled. “Come on. I didn’t ask for it. I didn’t even know it.”

“You may not have asked her outright, but you ended up right where you wanted. You never have to work again, do you realize that? You never have to care for anything. You can do whatever the hell you want to do while I clean up behind you. God.”

Holly was suddenly shaking with angry frustration. The fingers of one hand curled into a fist as she worked to keep from exploding. “Don’t lay that guilt trip on me, Hannah. You want to know what Mom thought of me? She thought I was stupid and useless and that I would never amount to anything because I wasn’t you. All my life I have tried to be who I am, but it was never good enough for her because I wasn’t you!”

“That’s bullshit,” Hannah said angrily. “She let you get away with murder.”

Holly drew a long breath. “I am not going to do this here, today of all days. Your baby is crying and I am leaving.” She walked out of the room, her head spinning with Mom’s last dig at her from the grave.

Chapter Three

Five months later

Hannah ran her finger down the names of doctors in the yellow pages. Family practice, family practice, OB/GYN. Family practitioners were no good; they made you pee in a cup these days. OB/GYNs were the worst, all of them on some freaking crusade to save women from themselves. Orthopedic doctors were suspicious right off the bat. Dentist, she thought. Dentists were so trusting. They would call in a scrip and an antibiotic before you ever saw them. But if you wanted a more than a few, it was best to call on a Friday, get enough to get you through a weekend, then forget the appointment they made for you on Monday.

Hannah glanced at the clock on the kitchen wall. It was already nine. She’d taken the day off of work to take care of this. Mason was down for his nap, and she had a window of maybe an hour to get it done. An hour wasn’t much time.

She pulled her sweater tighter around her and rubbed her hand under her nose. She made a mental note to call someone about the air-conditioning. It was freezing in the house, like the thermostat was broken. She’d checked it twice and it read seventy-eight. It couldn’t be seventy-eight. More like forty-eight. She shouldn’t be freezing in August.

Stupid pain clinic. She’d gone yesterday, but they said they had to have the clinic director sign off on her scrip, which Hannah had instantly known was trouble, because if there was the slightest delay in filling it, she would run low. And of course there had been a delay, they hadn’t yet called it in, and now she was dangerously low. The incompetence of people astounded her.

Pain clinics were generally easy, but Hannah didn’t like to going to them because they were full of little old ladies who needed their pain pills. Plus, a lot of the clinics would fill only one prescription—they didn’t want anyone’s abuse of pain meds traced back to them. Nevertheless, they never suspected her. One doctor wrote a scrip for her while he was on the phone. He never really looked at her … but then there was the doctor with the unpronounceable last name who had asked her if she was uncomfortable when she didn’t take the pain meds. Hannah had said no, that she was fine without them, and the doctor had suggested perhaps she try physical therapy instead, and Hannah had realized her mistake.

As she was leaving that clinic, a nurse with a rose tattoo on her neck pulled her aside. Hannah had wondered, why the neck? Why not the ankle? The shoulder?

“Listen, if you need something, you can call Brian.”

“Brian?” Hannah had asked suspiciously. “Who is Brian?”

The nurse with the rose tattoo on her neck had jotted down the number, and pressed it into Hannah’s palm. “He’s a friend,” she’d said softly. “He can hook you up, sweetie.”

“Excuse me?” Hannah had demanded haughtily. “Are you a doctor?” And she’d walked out with Mason.

But she’d kept the number. It was in her wallet now. Not that she would ever call it, no no no. She didn’t use pills like that.

Hannah’s phone rang, startling her. She picked it up and stared at the number. It was work. Hannah squeezed her eyes shut a moment against a pain in the back of her head. What part of Home with sick baby did they not understand? She punched the button on her phone and said, “Hannah Drake speaking.”

“Hey, Hannah.”

Great, just great, it was Rob Tucker, one of the partners. Rob was a talker. “Hi, Rob, how are you?” Just make it short. Don’t tell me about a case, God, please, don’t tell me about a case.

“I can’t complain. Hey, listen, I hate to bother you at home, but I’ve got a little bit of an emergency this morning.”

“No problem!” she said brightly. “What’s the emergency?”

“You said you left the files of the candidates we are interviewing this morning on my desk, but I must be blind, because I can’t find them anywhere,” he said with a chuckle. “We’ve got four lawyers sitting in the lobby and I don’t remember any of their names.”

This keeps happening. The pain behind Hannah’s eyes was excruciating. She vaguely remembered the files. What had she done with them? Okay, you had them in your hand just yesterday. “I am so sorry you can’t find them,” she said lightly. “I put them on your desk.” This was the third time Rob had to remind her about those damn applications. Why couldn’t his assistant handle routine hirings? Why did she have to do everything?

“Are you sure?” he asked.

“Positive,” Hannah said confidently.

“I know when I saw you in the hall yesterday, you had them in your hand. But I don’t remember you coming into the office.”

Hannah couldn’t think with her head in a vise, but she was fairly certain she’d left them on his desk, right next to the computer. “You must have been in a meeting, Rob. Do you think someone might have moved them?”

“I can’t imagine who,” he said thoughtfully.

The pain surged. Hannah gripped the phone, trying to stay focused.

“Oh, man,” Rob said suddenly, and laughed sheepishly. “Connie just brought them in. They were on her desk—Wait. What, Connie?” Hannah could heard Connie’s voice in the background. “Oh,” he said. “Connie said she found them in the copy room.”

“Oh?” Hannah could hear Connie talking still. Could they not have their conversation after she was off the phone?

“Well, we found them. So sorry to have bothered you at home,” Rob said. “Hey, tell Loren I said hello, will you? Is he doing all right? Working on some big cases?”

“You know Loren,” Hannah said with false cheer, as if Loren were always working on a big case instead of big tits. She’d recently found out about Loren’s third affair in their seven-year marriage, only this time when she confronted him, he didn’t buy her a diamond necklace like he had the first time, or get her pregnant like he had the last time. This time he told her it was over, and he’d walked out. That was two days ago. Maybe three. Or four. The days had kind of run together.

“He’s a real go-getter,” Rob said amicably.

He was a colossal ass. “Yep. So, listen, Rob, I really have to run. Mason’s home sick—”

“Yeah, sure. Sorry to have bothere

d you. But before you go …”

Hannah suppressed a sigh and rolled her eyes.

“Is everything okay?”

She stilled. Her grip tightened and she closed her eyes against the pain. “What do you mean? Everything is fine. I mean, Mason is sick, but you know, babies get these fevers—”

“Yes, right,” Rob said. “I don’t know, it just seems you’ve been a little distracted lately and I thought maybe you wanted to talk. I know your mom’s death must have been hard to deal with.”

Living was the hard part. Dying seemed easy. Just close your eyes that last time and sink … “No,” she said. “Everything is fine.”

That was followed by an awkward moment of silence. But then Rob said, “Well, good. I’ll see you tomorrow?”

“I’ll be there,” she said cheerfully, and clicked off. She made a face as she dropped the phone onto the bar with a clatter. “Idiot,” she muttered, and reached for a tissue. Her nose was always running now.

She bent over the yellow pages again, and felt a dull pain at the base of her skull. The pain was getting worse and worse, and Dr. Blakely was obviously incompetent if he couldn’t find whatever it was. She was sure it was a tumor or something like that, but no, Dr. Blakely said it was nothing worse than seasonal allergies. How was it that the world was populated with imbeciles?

Hannah turned the page to the dentists and, with her finger, started going down the list. Cosmetic dentistry … cosmetic dentistry … general dentistry. Harrison, DDS. Had she seen a Harrison before? The name sounded familiar, but then again, there was a Harrison at the office, too. Unfortunately, Hannah had forgotten her little notebook in which she kept her records of doctors and such at work.

One hour. You have one hour.

She picked up the phone and dialed Dr. Harrison’s number. “Hi,” she said brightly when the receptionist answered. “I’m kind of new to town and, wouldn’t you know it, I cracked a tooth.” She laughed, but realized that a person in pain wouldn’t laugh. “It’s really painful,” she said quickly. “I don’t have a dentist and was wondering if I could get in to see Dr. Harrison?”

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

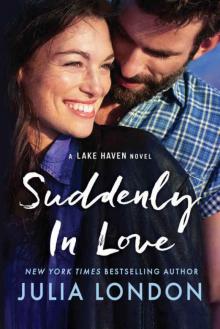

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)