- Home

- Julia London

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Page 4

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Read online

Page 4

“I did not hear your honest answer, madam. Do you prefer your admiration in word…or in deed?”

Her body was melting ahead of her brain. She could certainly understand why women fell under the man’s spell—those eyes were overpowering and the smile on his lips was so alluring that she feared she might very well expose herself to any number of potential scandals, right here, right now.

She looked at his mouth, but found no relief there, and madly wondered if he did indeed intend to kiss her. A kiss from Middleton! There was only one way to achieve such dizzying heights of trifling sport, wasn’t there? “In deed,” she said in a near whisper, then caught her breath and held it.

“Good girl,” he muttered, and moved until his lips were just a hairsbreadth from hers. He hovered there, and Ava prepared herself to be kissed by lifting her chin slightly.

But the man surprised her by licking her lips, and he could not have been more sensuous in doing so. With the tip of his tongue, he traced a slow path across the seam of her lips. Ava froze. It was the most sensual, decadent thing anyone had ever done to her, and it was so deeply stirring that she inadvertently released a small sigh of pleasure when he’d done it.

When she did, he lifted his hand to her jaw and gently angled her head just so, catching the sigh with his mouth as it passed through her lips. He drew her bottom lip lightly between his teeth and teased her body forward by slipping his free hand to the small of her back, persuading her forward while his tongue slipped into her mouth.

She felt as if she were falling toward him. She let him draw her into his embrace, opening her mouth to him, finding his waist with her hand. He was kissing her so thoroughly that she began to feel uncomfortably hot in her cloak, and with her free hand, she fumbled with the clasp and pulled it carelessly from her shoulders. He moved a hand to her shoulder, ran his palm down her arm, then across the bare skin of her bosom, and down, cupping her breast, squeezing it, his fingers brushing across the tip.

Ava gasped in his mouth; he moved her easily, pushing her down, so that she was on her back with her head propped against the side of his carriage. As his hands roamed her body, his mouth traced a wet path to her bosom, his tongue flicking between her breasts, his mouth pressing against the mound of flesh while his hand kneaded her.

When he lifted one breast free of the confines of her gown, Ava panicked and tried to sit up—but then he took the tip of her breast in his mouth, and she was falling again, sinking back into the squabs, her eyes closed to the storm brewing in her, her body on fire.

And then suddenly the coach came to a halt.

Middleton paused in his attention to her breast and glanced at the door. He sighed, calmly put her breast back into her gown as best he could, and kissed the hollow of her throat. He moved up, nipped at her lips once more as he pulled her to an upright position and draped her cloak around her shoulders, before lazily fading into the squabs of his bench across from her.

Ava was sitting in the same spot he’d left her, still leaning toward him, still feeling his lips on hers. As the door of the coach swung open, she looked out into the snowy night, then at Middleton.

He smiled, grabbed her hand, brought it to his mouth and pressed his lips to her knuckles, then let her go. “Have a care when you refuse a man’s offer to dance, Lady Ava,” he said with a wink.

Her mind had obviously deserted her, for all Ava could mutter in return was, “Thank you.” And then she concentrated on making her jelly legs move. With the considerable help of Middleton’s coachman, who caught her when she landed awkwardly, having forgotten her blasted shoe, she managed to exit the carriage without making a fool of herself. Once she was firmly on the ground, she pulled her cloak over her head and glanced back at the coach.

The marquis leaned forward and smiled through the open carriage door. “Good night, Lady Ava. It has indeed been a pleasure.” He glanced at the coachman. “See her safely to the door, Phillip,” he said, and then leaned back, all but his long legs disappearing from her sight.

The coachman shut the door and held out his arm to her. “If you please, milady.”

She pleased. Ava put her hand on the man’s arm and walked forward, bouncing unevenly to her right, her mind a million miles away from her shoe.

And when she was safely inside, and his carriage had gone on into the night, Ava removed the offending shoe and smiled softly. She couldn’t wait to tell her mother what had happened. Well, almost everything that had happened—she was not as foolish as that.

But that dreamy smile would be her last for some time, however, for her stepfather rushed into the foyer before she could divest herself of her cloak, his expression unusually serious. For a moment, Ava thought he somehow knew of her ride in Middleton’s carriage and meant to take her to task for it. But he uncharacteristically reached out his hand to her.

“Ava,” he said.

“Yes, sir?” she asked, surprised and a little frightened by the gesture.

“Your dear mother suffered a seizure of some sort just after supper. I regret to tell you that the physician is not hopeful.”

Three

C assandra Reemes Fairchild Pennebacker, Lady Downey, died suddenly at the age of five and forty years.

While it may have seemed to some that scarcely had the last clump of dirt been shoveled onto her grave when her husband, Egbert Pennebacker, Viscount Downey, left for France, in truth a month had passed. One long, interminable month during which Egbert suffered the tears of Cassandra’s daughters and niece while he fretted that his longtime mistress, Violet, had perhaps found another benefactor. He could not possibly know, for she was in France.

Frankly, Cassandra could not have picked a more inopportune time to die. Egbert, who had never been one to partake in the whirl of the social season, had been set to sail for France the very morning they buried his wife. Naturally, he’d sent a letter to Violet straightaway relaying the sad news and sending along sufficient funds for her safe voyage to England so that she might help him through a very trying time.

He’d yet to hear a word, not a solitary word. Not a note, not even a whisper of condolence in a month.

The uncertainty of what was happening drove him quite mad, and he paced his study more often than not, his stout legs and small feet taking him round and round the room while he nervously soothed the few strands of hair remaining on the crown of his head. In this state of acute anxiety, he could scarcely bear the company of the grieving girls. They moped about, rarely went out, and had covered everything in black. At supper just a few nights past, when he’d casually mentioned he’d not enjoyed asparagus soup in many years because Cassandra did not care for it, Phoebe burst into tears.

He’d lost his temper altogether.

“For Christ’s sake!” he’d bellowed with such force that his monocle popped right from his eye. “How long must I endure the incessant wailing in this house?”

“She’s not wailing, sir.” Ava quickly intervened as Greer handed Phoebe a handkerchief. “Surely you can understand the deep sense of loss my sister feels—indeed, we all feel. Our mother has only recently passed.”

Honestly, as if he needed to be reminded of that.

Egbert stared hard at a spoonful of soup for a moment before quickly stuffing it in his mouth and spooning more. Of course he didn’t begrudge them the time to grieve their mother properly—he, too, was sorry for her demise. After all, she’d been his wife for ten years and a tolerable one at that. He just wished they would do it in their chambers and not muddy his thoughts any more than his thoughts were already muddied. While her passing was sad, life did indeed go on, did it not?

He’d finished his meal in silence, but his mood had grown darker and darker as he eyed the three of them. They looked at him as if he were the one being unreasonable.

After supper, Ava had ushered Phoebe and Greer up to their suite of rooms and left him alone with his port and his cigar, but not before bestowing a disapproving look on him. That one was just like he

r mother. Egbert imagined they all despised him, and truly, he wasn’t so heartless, but Violet had been his little flower for nearly eight years. He could not bear the thought of losing her, too, and was desperate for an excuse to quit this endless mourning and leave London to learn for himself why Violet had forsaken him.

And that night, with the help of his port and a cigar, he landed on his excuse. Joy filled him, and he sprang from his chair and hurried to his study, his legs working hard to carry his rotund body as quickly as possible. Once there, he took pen and paper in hand and dashed a quick letter to Violet, filled with various declarations of adoration and devotion, and informing her that he would arrive in Paris in a fortnight.

The second letter he wrote was addressed to his spinster sister, Lucille Pennebacker, at the Lake District family estate, Troutbeck. In that letter, he insisted his sister come to London straightaway.

A week later, Egbert summoned his stepdaughters to the main salon. As he watched them enter his study swathed head to toe in the black bombazine of mourning, he mentally congratulated himself on being a charitable man, for what he would do for these three orphans was far and away the most charitable act they could expect from anyone. Certainly he would never turn out three orphaned debutantes, and he wished them no harm—but he wasn’t their father, was he? It did not, therefore, fall to him to ensure they found their way in this life. No, that responsibility had been Cassandra’s and now belonged to the girls’ kin, whoever that might be. That was precisely why he had urged Cassandra to marry them off before it was too late.

Alas, as with everything else, Cassandra had scarcely listened to him at all.

Pity that she hadn’t, for it would have spared them all a great deal of anxiety. Here were her precious girls, completely dependent upon his charity as they took their seats. They sat properly and smiled uncertainly at his sister, Lucille, who had arrived just this morning and who had, judging from the thin smile on her doughy face, already found her charges quite in need of her guidance.

Ava, the oldest and boldest of the three, looked from Lucille to Egbert and to Lucille again. She’d never really warmed to him, and he could see myriad thoughts and suspicions flashing in her green eyes. This one thought too highly of herself to his way of thinking, for she’d never agreed to any of the acceptable offers they’d received for her hand.

Egbert had wanted to accept the very generous offer Lord Villanois had made last Season, but Cassandra wouldn’t hear of it. “His fortune is hardly the sort I should want for our Ava,” she’d said with a sniff. “And he is far too fond of his drink. I shall not waste a perfectly good dowry on the likes of him.”

Egbert did not believe that Villanois was more or less fond of his drink than any other man, but Cassandra continued to make excuses, just as she had done when other men had come forward, for no man was good enough for her dear Ava.

Egbert rather supposed any offer would be good enough for her now that he was the final authority. Her carefree ways were a luxury Ava would know no more—she was well past a suitable age for flitting from ballroom to ballroom. She was of an age that she should have a child on her hip and one in her belly.

Ava seemed to sense his disgruntlement and glanced at Phoebe.

But Phoebe did not possess her sister’s intuitive sensibilities, and merely smiled at him. He’d always thought Phoebe was too trusting of mankind in general, really.

“May I introduce my sister, Miss Pennebacker,” he said, gesturing lamely to Lucille.

The three young women nodded politely; Lucille actually stood and curtsied as if they were royalty, saying, “It is a pleasure to make your acquaintance.”

“Thank you,” Ava said.

“I’ve rung for tea,” Egbert said, and impatiently gestured for Lucille to sit. She sat. “It shouldn’t be a moment.” He idly watched Phoebe as she situated her gown just so. She was similar to her sister in size and shape, but her pale blond tresses were lighter, her eyes a bluish green. Privately, Egbert always thought her the most handsome of the three and had believed her time on the marriage market would be quite short. Unfortunately, Phoebe was too shy for her own good, and to make matters worse, she had a propensity for dreaming—her head was always in the clouds, or in a book, or in some sort of artistic endeavor—and he rather supposed that was why she hadn’t received any offers.

When he’d expressed his concern about the lack of offers for Phoebe to his wife, Cassandra had brushed his concern aside with the ridiculous excuse that Phoebe had a special talent for art, and to marry would rob her of the freedom to express herself. “If she were forced to marry, any husband would keep her pregnant and in the nursery before he would allow her to paint, mark me,” she’d said with much superiority.

Egbert didn’t understand his wife’s reasoning, for that was exactly where they all belonged.

A commotion at the door startled him from his thoughts.

“The tea has come,” Lucille announced, and bustled forward with her big hips bouncing along behind her to meet Richard, the butler, as he brought in the tea service.

Ava and Phoebe turned to see what she was about, but Greer sat still, looking curiously at Egbert. That was because Greer was inherently a rather clever and curious girl. She was dark where her cousins were light, her hair the color of coal and her eyes dark blue. She was as handsome as her cousins but in a subtler way—a man had to look twice to see the beauty in her.

When Greer’s mother, Cassandra’s baby sister, had died, her father was quick to remarry, hoping to gain the son he’d been deprived of with his first wife’s death. Cassandra had taken Greer in, and as far as Egbert knew, Greer’s father had never taken an interest in her. Therefore, Greer was what he considered the poor relation. Yet Egbert was perhaps fondest of her, for she shared his practical, intelligent nature.

Unfortunately, because Greer was a poor relation, Egbert’s charity toward her had been overextended. Certainly there was another person in the illustrious Fairchild family who could bear her cost, or at the very least, see her married.

Greer had received offers, too, but by the time they had been brought round, Egbert had realized Cassandra meant to keep them all with her, and had lost interest in the excuses she threw up in Greer’s defense.

An inadvertent smile creased his lips as he looked at the three of them now. He intended to remedy their unmarried situations just as soon as he returned from Paris. They would be married to the highest bidder in turn, or, if they refused, sent to live with relatives. He had no desire to support them any longer than he must. For goodness’ sake, he already had the burden of Lucille.

The three young women looked at him expectantly as Lucille poured tea.

Egbert sighed, pressed his fingers to his temples, and leaned back in his chair. “Very well, then, we are all settled and I shall not make preamble. The question is simply put: Now that Cassandra has died, what are we all to do? I shall tell you what I am to do. I have found it very difficult to mourn my wife properly, what with all her things and her children about. It’s been very…” He racked his brain for a word, and finding none, repeated, “…difficult.”

“You poor dear!” Lucille said, and put her hand atop his, squeezing gently. “I had no idea you were so aggrieved.”

Egbert glanced down at her pudgy hand, then glanced up at her face. Lucille promptly removed her hand.

“If I may, my lord,” Ava said, leaning forward slightly in her seat. “Perhaps we might spare you the, ah…difficulty. We’ve discussed it, and we should like you to know that we’d be willing to reside elsewhere if it pleases you.”

Oh? This was an interesting twist—something completely unexpected. “Elsewhere? And where would that be?” he asked, almost gleefully.

“We thought a small house in Mayfair. Nothing too grand, of course. And we’d require only Beverly, our lady’s maid. Oh, and a housekeeper, of course.”

Egbert was taken aback—Cassandra had never mentioned that these three had funds of th

eir own. He couldn’t see how it might even be possible. Certainly if he’d known, he would have insisted on the details so that he could manage it for them, for really, what did three young women want with their own funds? “Your own residence,” he repeated carefully.

Ava nodded.

“And I suppose you have sufficient funds?”

Ava exchanged a look with her sisters. “I’m rather certain that we do.”

But she did not look entirely certain because she was, obviously, a woman, and women were not meant to handle finances. “Could you then, perhaps, become certain?”

Ava blinked. “I beg your pardon?”

“How can you possibly hope to lease a residence if you don’t know how much money you’ve got?”

“Oh dear, Egbert! That’s so vulgar!” Lucille chastised him, earning an impatient glance from her younger brother.

“It is a matter of necessity that it be discussed, Lucy,” he said impatiently, “and I can think of no way to discuss it other than to utter the words aloud!”

“I beg your pardon, my lord,” Ava quickly interjected, “but you are in a much better position to know about the, ah…money…than am I.”

Now she was confusing him. “Me? How could I possibly know?”

“Well,” Ava continued, looking just as confused, “we…we don’t know how…how much she had, but we rather supposed there is enough to take a modest residence.”

It was suddenly clear to him, and Egbert, charitable man that he was, almost came out of his chair in his eagerness to lean across the desk and pin the bold one with a stern look. “Are you suggesting, miss, that I lease you a residence?”

Ava blinked. “I, ah…I just assumed that you would—”

“Then you assumed incorrectly!” he bellowed. “Clearly you do not understand what a financial and social burden the three of you present to me!”

“But we do,” Ava hastily sought to assure him with Phoebe and Greer nodding furiously alongside her. “That is why we thought to offer to go elsewhere.”

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

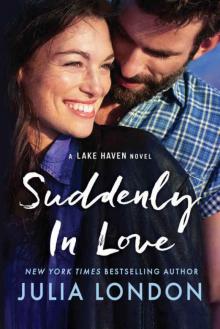

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)