- Home

- Julia London

Summer of Two Wishes Page 6

Summer of Two Wishes Read online

Page 6

“Liar,” she said, smiling sheepishly. “I’ve barely strung a coherent sentence together. You are the one who’s been great.” He’d been charming when he needed to be and at ease throughout, squeezing her hand when he felt the small tremors in her and pulling her up when she wanted to sink. On those occasions when he was interviewed alone, she marveled at how strong and how relaxed he looked, whereas she’d found the attention excruciatingly painful.

“I’m serious,” he said, and casually freed a strand of her hair from her collar. “It’s not so tough for me. All I had to do was say it was great to be home. They were putting the hard questions to you.”

“Impossible questions,” she muttered, and averted her gaze a moment, her mind full of complicated thoughts. “It was hard to find the right words to respond with. It’s even harder finding the right words to say all I want to say to you.”

Finn’s jaw flinched. “You seemed to find the right words.”

“No, I mean…I didn’t tell you how sorry I am for everything, for what you’ve been through, for what you came home to. And how indescribably happy I am that this is real, that you are really here. Who would have dreamed this could happen?”

“I did. I dreamed something like this could happen every day.”

He said it in a way that suggested he thought she should have, too, and guilt stabbed Macy—she hadn’t dreamed hard enough or long enough. “I wish I could have dreamed it,” she said softly, “but I never could seem to stop having nightmares about how you must have suffered when you died.”

Pain skimmed his features, but Finn’s expression quickly shuttered again. Macy suddenly realized that was what she had been seeing these last two days—he’d been hiding behind a mask.

“I wanted to let you know that I am going to stay at Mom and Dad’s for a few days,” he said. “Brodie says there’s not much at the ranch to go back to. He says the house is empty and the cattle and horses are gone. Dogs, too.”

His voice was cool, and Macy couldn’t blame him. It was just something else he’d thought he’d be coming home to. The horses had not only been his business, they’d been part of his family. He loved them; he had a gift for connecting with animals, especially horses.

When Macy had first met Finn, he’d lived alone with the stray dogs he took in on the three hundred acres of the Two Wishes Ranch. He and a grizzled Mexican named José Banda trained cutting horses. Cutting horses had once been used to cull sick cows from herds of cattle, but now they were used mostly in competitions to separate calves from herds. Macy hadn’t known any of this, of course, until Finn had taught her. And she’d learned that a good cutting horse could sell for thousands of dollars.

José had taught Finn everything he knew about training horses, and the two of them became known as some of the best trainers in the southwest, their services in high demand. They’d kept about three dozen cattle on the ranch for training purposes, and two high school kids had worked half days with them, learning the business.

But training a horse took time, and money was slow to come in. When they’d first married, Macy had just graduated from college and had secured a position as a social worker with a nonprofit agency that mentored kids in the foster care system. Her salary was laughably low, but she loved the work. She’d been good at it, and her caseload grew. It eventually got so big that she spent more time driving around central Texas than she did mentoring. It seemed like the only thing she managed was a quick check on the welfare of the kids on her list—there was no time for anything else. She didn’t feel like she was helping anyone but the oil companies.

Finn convinced Macy he needed her at home. She had a better head for numbers and bookkeeping than he did, so Macy quit her job and stayed home to keep the books. Unfortunately, that didn’t take very long. She ended up spending a lot of time hanging around Finn, watching him work.

Finn had acquired three cutters of his own, which he entered in competitions for a little extra money. Those horses had been with Finn longer than Macy had, longer than any of the stray dogs he’d taken in. It had killed Macy to sell the cutters, but there was nothing to be done for it. Even if she could have afforded their upkeep, she couldn’t care for them by herself.

When he’d left her to join the army, Finn had told Macy the ranch would take care of itself. For a few months, it had. But then the officers had come and told her Finn had been killed. And then the cattle got sick. The veterinary bills were high, even with Finn’s brother Luke providing the service and Macy paying only for the medicine. A big chunk of the death gratuity provided by the army had gone to pay bills and taxes. Macy had also received life insurance for Finn from the government, but her mother had been frantic that she would spend it all on the ranch and had made her put a chunk of it in mutual funds for her future. That was a great idea, but the market had taken a nosedive since then, and she’d lost about thirty percent of it. The two high school kids graduated, and then it was just Macy and José, and…and she couldn’t do it.

One day, under a hard Texas sun, Macy told José of her decision to shut down the cutting horse business. She’d given him six months pay as severance. She never knew if it was the heat or the news that made his eyes water, but José had said little more than “Gracias,” and had packed up his beat-up, boxy, old red pickup. She’d heard he’d gone on to a vaquero job south of Dallas-Fort Worth.

Macy looked at Finn now with all of that running through her mind and said, “I am so sorry.”

“I understand,” Finn said, but his jaw was clenched. “It was too much for you.”

“It was hard, Finn. It was a lot harder than I ever thought it could be. The cattle had to be fed in winter, and that year we had a drought, so we had to buy a whole lot more feed than usual, and the horses needed to be watered, and then the cattle got a respiratory disease…” Her voice trailed off. It had all started one night when she’d heard an awful howling outside. She went out and discovered one of the dogs—a big dog they called Tank, who easily weighed one hundred pounds. He’d eaten something or been bit, she didn’t know, but he was in distress. He was too heavy for her to lift, and Macy had cried and cried waiting for Luke to come. The dog had died with his head in Macy’s lap before Luke could get there.

A few weeks later when the first calf got sick, she’d felt completely helpless.

“Your dad and Brodie and Luke tried to help out when they could,” she said quietly. “But they have their own lives and Luke was opening the clinic, and Brodie had started a new job, and they couldn’t come around as often as I needed them, and then some of the cows got sick and we had to destroy some. The ranch was bleeding money and I couldn’t seem to stop it.”

“No need to explain,” Finn said.

“No, I need to explain,” she insisted, desperate to justify a decision that had seemed so right at the time. “I know better than anyone how much the cutters meant to you. It killed me to do it, you have no idea. I felt like I was abandoning a part of you.”

He snorted and glanced impatiently over his shoulder. “You mean the part of me you could remember?”

“What?”

Finn looked up; his eyes were flashing with…anger? Disappointment? “Just going back to what you said, Macy. You said I started to disappear from your memory. My hands, my feet…So when did I disappear completely? When you sold my horses?”

“That…that is so not fair,” Macy said, her voice low. “You are misconstruing what I said. You never disappeared, Finn, not for a moment. You were always in my thoughts and in my heart,” she said, pressing her hand against his heart.

He covered her hand with his, squeezed it. “Until Wyatt Clark showed up, anyway,” he said.

She pulled her hand from beneath his. “Please don’t do that. You cannot begin to understand how deeply I mourned you and how ecstatically happy I am that you are alive.” But as the words left her mouth, she realized how hollow they must sound. “Losing you hurt worse than anything I have ever felt. People would ask,

How are you coping, Macy? and I’d say fine. But I wasn’t fine. I wasn’t coping. And I didn’t tell anyone because words couldn’t describe the pain I was feeling.”

Finn nodded. “You know the thing I keep wondering? I wonder when you decided to move on. How long did you mourn me—mourn us—before you were ready for someone else? You’ve been married seven months, so somewhere between three years ago when you thought I died and seven months ago when you remarried, you said, okay, I’m ready,” he said, gesturing between those two invisible dates.

“You’re being unfair.”

“Macy.” He sighed and raked a hand through his hair. A chunk of it fell back over his eye. “I’m only trying to understand how long you gave it before you let me go and let him in. It’s a fair question.”

“Finn, stop—”

“I can’t help but ask! You helped me get out of there! I had this fantasy of you, and all the things we’d do when I was free. I’d imagine how many dogs and horses and cows we could fit on the ranch.” He laughed wryly and looked down. “I had this fantasy that we’d travel, and we’d have this great life with lots of kids, and I imagined Christmas mornings with them, or teaching them to ride, or watching them play football or act in one of those little kid plays they do in elementary school.”

He looked up again, his expression sad and angry. “But then I came home and found you married to someone else, and I’m still trying to wrap my mind around that. Sorry if I ask some hard questions, but I think I’m entitled to know.”

Macy’s belly began to roil.

“Did he come around looking for a grieving widow?” Finn asked curiously.

“No,” Macy said. Wyatt wasn’t like that. “Dad introduced us.”

Finn snorted at that. “So the old man just showed up one day and introduced you to your next husband?”

“Finn, please,” Macy said, pressing a hand against her abdomen. “We had buried you.”

“Just tell me how long you waited after you thought I’d died before you hooked up with Clark.”

As if she’d just turned him off and Wyatt on one day, could name the exact moment she’d let go the memory of him and allowed herself to love Wyatt. “Roughly two years,” she said tightly. “I spent two years thinking of you every moment of every day. Mourning you. Wishing I had died with you. And then…then one day I didn’t want to worry or die anymore. I don’t know how it happened—it just happened.”

“Wow,” Finn said, his gaze sliding over her. “Two years.”

His indignation suddenly angered her. “You act as if I should have assumed you were alive in spite of all the evidence to the contrary! I am sorry if I can’t describe the loss and the despair I felt to your satisfaction, Finn, but believe me, there were days I never got out of bed. I spent many, many long nights surfing the Web, putting your picture up at every fallen soldier Web site I could find along with a personal tribute because that was the only thing I knew to do to soothe my grief, and that didn’t even touch it. There were days I didn’t eat. There were very long days that I didn’t do a damn thing but wander around the house, looking for you. Cows were outside calling for food, and I didn’t care. There were entire days when I did nothing but worry that I hadn’t said good-bye to you the right way. I’d said good-bye like you were coming back, not good-bye like I’d never see you again, and I couldn’t do anything but worry about it.”

“Jesus—”

“I got the black boxes with your stuff from the army and I thought I would have something that had your scent, something I could touch and hold on to, but you know what? They washed it all! I couldn’t smell anything but detergent! And you know what else? I was very angry, especially with you for joining the army to begin with. What the hell, Finn? Why did you have to go? Why did you have to risk everything that we had?”

Finn didn’t speak.

“All that sorrow and anger almost buried me,” Macy heatedly continued. “Ask anyone here. So forgive me if one day I decided my life was still worth living, even without you. That’s right, I tried to find a way to live my life without you. What else was I supposed to do?”

He looked stunned. Let him be stunned, Macy thought bitterly. “I’m sorry if I didn’t grieve correctly, but no one gave me a manual for that, any more than they gave me a manual for how to put everything back the way it was when my lost husband turned up blessedly alive.”

She moved to pass him, but Finn stopped her by taking her arm. “Before you flounce off, I want to tell you something.”

Macy tried to remove her arm, but his grip tightened.

“I didn’t get a rule book either,” Finn said quietly. “I never even thought of the possibility you might have remarried, can you believe it? Maybe that was dumb, but I didn’t, and now I don’t really know what I’m supposed to do with you. Am I supposed to accept that you moved on? I’ve tried, Macy, but it’s not that easy for me.”

Macy glanced down. Her hands were shaking. “Me either,” she admitted in a whisper.

He caressed her arm with his thumb. “I’m not trying to upset you. But I’m a plainspoken man, and I’m just going to tell you straight up. I can’t stop thinking about you. Hell, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about you since the moment we met, but now I can’t stop thinking of you with him. It makes me feel sick. I love you, Macy, and I didn’t come this far to lose you. You need to know that. You need to know that I want you, and I’m not going to give up on us until you tell me to, and even then, I’m not sure I can. Beyond that, I don’t know what else to say.”

There was a time those words would have melted her right into his arms. This evening, they stirred an unbearable yearning for something that was bigger than desire. Those words went right to her heart and warmed it, hurt it, made it beat like it hadn’t beat in years. They were almost too intense after the emotional swirl of the last week; another wave of nausea came over Macy. She pulled her arm free of his grip, gulping for air. “Excuse me,” she said, and hurried past him to the bathroom.

Inside the small bathroom, Macy gripped the edge of the sink, her eyes closed, her belly churning. She was a horrible person. He was home, alive, and he still loved her, and she felt wobbly. It reminded her of the physical pain she’d felt when she’d lost Finn—too great to endure.

When the nausea passed and she emerged, Brodie was standing outside the door, his arms folded over his chest. “Did you tell him about Two Wishes?” he asked quietly.

The ranch—oh God, the ranch. “No,” she said, and when Brodie looked accusingly at her, she added, “I don’t need to tell him anything, Brodie. I am going to fix everything. He doesn’t need to know. What’s the point?”

“You’re making a mistake, Macy,” Brodie said. “He should hear it from you.”

“Just trust me, will you?” Macy asked with exasperation, and ducked around him. “Everything is under control,” she said as she passed, and ignored Brodie’s dubious expression.

8

Finn’s head and heart were racing, giving him an excruciating headache. He lost sight of Macy after their talk; Brodie said she’d left with her mom.

He wanted out of there, away from all the peering eyes, the smiles, all the hugs and pats on the back, proclaiming him a hero. He was starting to feel claustrophobic. Antsy.

At last, Finn said good-bye to all the military personnel and Friends of Fort Hood, the reporters, his extended family, and God knew who else, and piled into his father’s Chevy Suburban with his entourage, headed for home.

He rode in the front passenger seat, a seat of honor, apparently, as his mother had insisted he take it. But as the Suburban pulled onto Highway 71, they were met with an onslaught of lights rushing by in the opposite direction. The lights were blurring into each other and Finn blinked, trying to focus. He instinctively braced his arm against the frame of the car. He didn’t like riding in the front, sitting up high with nothing but glass around him. He felt dangerously exposed and defenseless. He tried to tell himself this was Aust

in, not Kabul, but it didn’t help his anxiety.

He was so tense he could scarcely respond to the many questions his brother Luke put to him, could not concentrate when Mom talked about the family reunion she wanted to have as soon as possible. Finn could feel the trickle of perspiration running down his back as cars darted around his father’s lumbering machine. His heart lurched every time a dirty little white car swept past them—they reminded him of the car that drove into Danny and him, and there seemed to be an inordinate number of them in Austin.

By the time they reached the old home place, his nerves were frayed. He spilled out of the Suburban and quickly walked away from it, pretending to get a good look at the house where he’d grown up, but gulping for air before anyone could notice. The house, a fifties-style ranch, was surrounded by scrubland and flanked to the south by a barn bigger than the house. A windmill that didn’t pump water anymore stood on the north side. The place looked exactly as it had the day Finn left, as if time had stood still on this little ranch.

Someone put a hand on his shoulder; Finn flinched and whirled around.

“Hey,” Luke said, quickly lifting his hand. “I didn’t mean to scare you, man. Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” Finn said. “I was just wondering—you think Dad has any whiskey?”

Luke grinned. “Are you kidding? It’s still under the oil cans in the garage. I’ll get it and meet you on the back porch.”

Finn grabbed his rucksack from the back of the Suburban and walked inside the house.

“Finn, you’ll be in your old room,” his mother called from the kitchen. I’m going to fix us some sweet tea.”

Inside, the house looked the same as it always had. It was built of limestone with a beamed ceiling in the living room and a linoleum floor in the kitchen his father had been promising to replace for ten years. One long corridor led to all the bedrooms.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

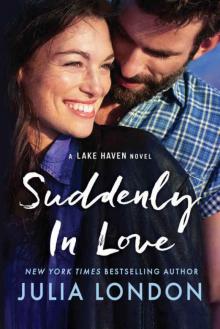

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)