- Home

- Julia London

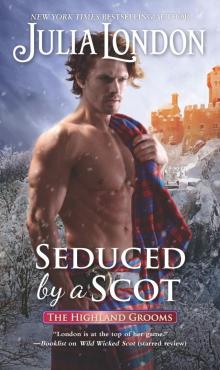

Seduced by a Scot Page 6

Seduced by a Scot Read online

Page 6

“What’s happened to her, then?” Gavin asked timidly, his dark hair sticking up in several directions.

“She’s gone off, that’s what.”

“By herself?”

“Aye, by herself,” Nichol bit out.

Gavin’s eyes rounded.

Nichol stomped down to the brook, thinking. He looked around, for any sign of where she might have gone. There was the horse’s hobble lying on the ground. But the saddle was precisely where he’d left it. He shook his head at her audacity.

He knew where she was heading, if she could manage to determine the direction. He knew because she had done quite a lot of talking yesterday. She was so angry, and she wanted to give Miss Garbett a piece of her mind. Had she not said so more than once? Nichol didn’t pretend to understand how a woman’s mind worked, but he’d been with enough of them to know that a woman scorned was like a dog with a bone.

He was entirely confident that Miss Darby was on her way to Stirling just now.

There was no question that he had to go and fetch her. He couldn’t have her appear in Stirling on the back of a horse with nothing but her fury—his reputation would be ruined! Not to mention he would lose his fee. Bloody stupid lass. Stubborn wench.

He squatted down and splashed water on his face. She would have kept to the roads. He could ride through the forest and catch her before she reached Stirling. But he couldn’t catch her if he was riding with the lad.

He stood up, hands on hips, and stared at the rising sun.

What was he to do with the lad? He couldn’t send him back to Aberuthen—the inn there was too bleak. There was no question that he could not return to Rumpkin’s house of horrors. Nor could he send the lad on to Luncarty, as that was too far away—Nichol didn’t trust him to make it there on his own without a horse.

There was one other option, unthinkable until this moment—Cheverock, the home where he was born. A half-day’s ride from here at most.

Nichol had been toying with the idea of paying a call to his boyhood home, but to appear at Cheverock in this way after all these years was not what he wanted. Ivan would not understand a lad showing up and claiming to have been sent by Nichol. The last Nichol had seen Ivan, he’d not quite reached his majority. What would he think? And why had Ivan grown silent? Had he forgotten Nichol?

He hoped it was no more than that.

But he sensed it was much more than that. All the messengers had been turned away.

Never mind that now—this sudden development would force the issue for Nichol. He had no other viable choice so it would seem at long last, he was going home.

Gavin could walk there and arrive by nightfall if he set out now.

Nichol glanced over his shoulder—Gavin was watching him anxiously, twisting the corner of his plaid that he’d draped around his shoulders. What was he, fourteen years? Fifteen? Too young for this, that much was apparent.

Nichol turned around, and the lad blinked. He clearly suspected the news for him would not be good.

Well, then, there was nothing to be done for it—Nichol was in a corner. He trudged back to the campsite, stood with his legs braced apart, his arms folded across his chest, and eyed the lad. After a moment, he said, “I must go after the lady, aye?”

“Where’s she gone?” Gavin asked.

“I canna say for certain, but I’ve a good idea where,” Nichol bit out. “She’s got a good head start on me, aye? I need move with haste.”

Gavin nodded. “I’ll gather our things.”

Nichol stopped him with a hand to his shoulder. “Gavin, lad, I canna catch her with two of us on the horse.”

Gavin’s brown-eyed gaze filled with uncertainty.

“I mean to send you off to a place where you may wait for me.”

Gavin’s lips parted. “Where?” he asked, his voice faintly tremulous.

“The seat of the Baron MacBain.” Perhaps Nichol was imagining things, but Gavin looked suddenly very pale. “I grew up there,” he explained. “You will speak to my brother, Ivan, and he will see that you are looked after until I come for you, aye?” At least he prayed that was the case.

“Should I no’ go to Stirling?” Gavin pleaded.

“It’s too far to reach on foot, aye? Do you know how to shoot, lad?”

Gavin shook his head. He was beginning to breathe heavily, almost in a pant. Diah, but Nichol wanted to shoot something just then. He would not like to be without his pistol, but he would not rest knowing the lad had nothing with which to defend himself. So he withdrew his pistol from his waist and held it out to him. “Watch me closely, then. We’ve no’ much time.”

He showed Gavin how to load it, to cock it, to fire it. He made him do it three times until he was satisfied that he’d at least not shoot his own foot. “You’ll no’ need it, but you ought to have it. Now off with you, straight up the road. By day’s end you will come to an old castle ruin. The road forks there—turn east. You’ll be two miles from Comrie. Cheverock is about two miles more.”

“What if I get lost?” Gavin asked, his voice shaking now.

“You’ll no’ be lost. Look at me, Gavin,” he said, and went down on one knee before him. “You canna get lost if you follow the road. Walk until you reach the old castle ruin, then take the eastern fork,” he said, pointing east. “Tell Ivan I’ve sent you and I’ll come for you by week’s end, aye?”

Gavin was trying very hard not to cry. He nodded and looked at the gun in his hand.

“Look here,” Nichol said softly. “You’re a brave lad and a clever one, you are. You have everything you need inside of you, Gavin. Everything is there,” he said, tapping his chest. “You donna need me, no’ really.”

“What if they donna believe me, then?” he asked through a sniffle.

It was a fair point. Nichol suddenly stood and went to his satchel. He looked inside, in a pocket there, and withdrew a ring. It was an insignia ring, one that had belonged to his grandfather, a man he remembered with fondness. He turned back to Gavin and pressed the ring into his palm. “Give my brother this. Tell him I’d no’ ask for his help if it were no’ imperative. He’ll believe you.”

Gavin looked at the ring, then slowly put it in his pocket.

“There’s a good lad,” Nichol said. He patted him awkwardly on the shoulder, then handed him the bags. “There is food and ale. Put your pistol here, aye? If you see anyone on the road, hide in the forest until they’ve passed. You’ve nothing to fear, Gavin.”

He hoped to God above that was true. Nichol didn’t know what the lad might expect when he reached Cheverock, as the estrangement between him and his father, and perhaps his brother, made it impossible to know. But he believed Ivan to be a decent man. He would not turn the lad out.

Gavin looked up, and Nichol would have kicked himself squarely in the arse if he were able. He had no desire to send Gavin off into the deep of Scotland all alone, any more than he desired to ride like a thief across Scotland to catch Miss Darby before she ruined everything for him. “I must go—I canna risk losing the wench, aye? Go as quickly as you can. You’ll reach Cheverock by nightfall if you donna tarry.”

He turned away from the lad whose eyes were as big as moons, grabbed up his things and stuffed them into his satchel and strode to where the lone horse stood. In minutes, he was saddled. He glanced back at Gavin, who had at least gathered his bedroll and the bag. Nichol threw himself on the back of the horse and reined him around. “God’s speed,” he said to Gavin, and set the horse to a trot, which he would turn to a run as soon as he reached the road.

Miss Darby, that wee half-wit, would sorely rue the moment she stole his horse and escaped. Aye, he would make damn certain of it.

CHAPTER SEVEN

EVERY MUSCLE, EVERY SINEW, ached in Maura. She’d had to cling to the horse so she’d not fall off. Her progress was achingly slow��she was afraid to give the horse any room to run, afraid she’d be bounced right off and onto her arse and lose him.

How far could it possibly be to Stirling? She’d been sent to Aberuthen by carriage, but they’d reached it within a matter of a few hours. And yet she felt as if she’d been riding all night and all day. She’d kept to the road, so she didn’t think she was lost. Could she have possibly gone the wrong direction? Hadn’t Mr. Bain very clearly pointed in this direction? Still, it had been awfully dark when she’d sneaked away in the predawn hours, and perhaps she’d gotten a wee bit turned around.

She hadn’t wanted to leave the warm cocoon of Mr. Bain’s body and blanket. She hadn’t really wanted to leave the safety of him, either. But she’d made herself go, the desire to have her necklace compelling her. Frankly, she couldn’t believe Mr. Bain and the lad had slept through her departure. It had taken quite an effort to unbuckle the heavy hobble as her fingers had turned to ice. The horse, the smaller of the two, had snorted over his shoulder at her, annoyed with her clumsy attempt. But at last she’d undone it, and had tied a rein around it’s neck—she’d been too afraid to attempt the bridle—and had led the horse along the brook until they reached the road.

It had taken her several attempts to put herself on the horse’s back. She’d tried jumping up, grabbing his mane, but he kept moving away, unwilling to participate in such mischief. And then she’d spotted a rock near the edge of the road, and at last, with the help of that rock, she was able to claw her way onto the horse’s back. At which point she found herself lying flat against him, holding on to his mane, the rein having been dropped as she’d tried to mount. She would not risk losing the horse by getting off to retrieve it. She had kicked the horse in the flank, and off they’d trotted.

How she wished for a saddle! But to take one of them would have been useless—she didn’t know how to saddle the horse, didn’t know if she could lift the thing over her head.

Eventually, she’d felt secure enough to sit, but she’d left the gait up to the horse. They’d moved along, sometimes ambling, sometimes trotting. Once even stopping when the horse seemed rather determined to have a rest.

The sun was high in the sky now, and Maura passed the slow progress picturing the scene when Mr. Bain woke to find her missing. She imagined he’d been quite cross, as men thought themselves superior to women in every way, and he was undoubtedly the sort to despise being taken for an utter fool by a woman. The question was, would he be angry enough to follow her? He seemed a proud man, aye, but she didn’t know if he was too proud to chase after a woman he scarcely knew. He’d done his duty after all. He’d removed her from Rumpkin and he’d surely collected his fee. And while she was certain beyond a doubt that he’d been cross when he discovered her missing, he also seemed unflappable. Detached.

No, he’d not come after her, she decided. He’d pack his books and tell the lad the day was fine and they might carry on without her.

The horse snorted and tossed its head; Maura glanced up and made a little cry of joyous relief. Below her, she could see the chimneys and rooftops around Stirling castle. There was a bridge across the river, and at the bridge, an inn with a public house. She would stop there and try and repair her appearance as best she could. And she’d have to think of a plausible explanation for her return to Garbett House. Aye, I’ve come back, Mr. Garbett. How could you send me off to such a reprehensible man, I ask you? I’ve been a good and loyal ward to you, sir, and I’ve tried my verra best to stay out of Sorcha’s light. How dare you impugn me, how dare you dishonor me as you have!

No, that wouldn’t do. Mr. Garbett generally did not care to be wrong.

Mr. Bain removed me and then left me! He said he’d invented the whole thing, and that he hadn’t the time to take me anywhere. He said that I might do as I please but I could no’ return home. What was I to do, then?

Better. But still highly implausible. Mr. Bain had come at the recommendation of the Duke of Montrose. Wouldn’t Mr. Garbett take his complaint directly to the duke?

We were set upon by thieves and they took Mr. Bain! I managed to escape and came straightaway home, as I knew you would want me to do.

That might work.

The horse suddenly began to canter. He probably sensed the end to his ordeal was near or had caught the scent of oats. But whatever the cause of his sudden burst of enthusiasm, Maura gave a little shriek and grabbed onto his neck to keep from being tossed off as they passed through a copse of trees.

She saw the horse’s interest then—just ahead was the public inn, and two horses at the trough that hers was determined to join. If she ever saw Mr. Bain again—which she would not, but if she did—she would compliment his very fine horse and thank him for the use of it.

At the trough, the horse muscled in between the other two. As he dipped his head to drink, Maura slid off his back, wincing when she landed. Her legs felt as if a thousand knives had scraped up the insides of them. Her hair was loose, and she wrapped it around her fist, then tied it in a knot. She had to find some place to tidy up—she could hardly walk into the public house looking as if she’d been dragged through the forest. She tried to see over the horses. There was the inn, its door standing open, through which she could hear the voices of many. Beside the inn a smaller building. An office, she guessed, where mail and passengers paid for the coach. And behind that, a slightly larger building. The stables? That was it, then. She’d slip inside, attempt to tend her hair and shake out the wrinkles from her cloak and gown.

Maura stepped out from between the horses, glanced nervously toward the public house, drew the hood of her cloak over her head and hurried around the trough and down the path where horses were brought up from the stables. She quickened her step, and at the corner of the office, she paused to take one last look behind her before turning the corner, but was suddenly yanked backward by an unseen force, and a gloved hand clamped down over her mouth.

Maura desperately tried to find her footing, but was lifted off her feet, spun around and shoved up against the wall of the office.

It all happened so quickly that she hadn’t had time to breathe, much less scream, and when she looked into the pale green eyes of Mr. Bain, her heart tried to leap through her throat and flee.

His eyes were shimmering with undiluted fury. He held her with his body against the wall, his hand firmly anchored her mouth closed, and with his free hand, he lifted a finger. “No’ a word, aye? No’ so much as a sound from you, or I will bring the men of the public inn down around your ears and tell them you’re a whore who stole my purse.”

She would have gasped with shock if she’d been able.

“Do you understand me, then?”

She didn’t know how she was supposed to answer seeing as how he was holding her mouth shut, but managed to nod.

He slowly let go his hand at her mouth, but kept her pinned to the wall. It was rather awkward—he was mere inches from her, half his body pressed against half of hers. “I’ll no’ scream, I swear it,” she said. “Will you step back, then?”

He laughed, and the sound of it was not pleasant. “No, you bloody wench—I donna trust you.”

“At least I’ve no’ accosted you against your free will.”

“No, you’ve gone sneaking off in the dead of the night. What in bloody hell were you thinking, then?”

“I owe you no explanation, Mr. Bain, as you have no say over me, but obviously I was thinking I needed to escape!” she said incredulously. “Do you blame me? I donna care to go and marry your Mr. Whatsit.”

“Have you a better idea what to do with you?” he scoffed.

“As it happens, yes!”

He snorted. “You may trust me that confronting Miss Garbett with hysteria is no’ a better idea.”

Fury replaced her fright, sweeping through her with such force that Maura was surprised it didn’t lift her off her feet. “Hysteria?��� she repeated loudly, and kneed him as hard as she could just below his knee.

“Ouch. Damn you, that hurt.”

“I donna suffer from hysteria—”

“No, your malady is madness, quite obviously. I am trying to warn you that confronting her will no’ improve your—”

She shoved him away from her. “I’m cross, Mr. Bain! Verra cross! You canna imagine how it feels to believe yourself part of a family, at the verra least a valued servant one moment, and then in the blink of an eye be cast out as if you are nothing to them! To be thought of so little that all your things are taken from you! To be made a vagabond! I am cross,” she said again, and to her horror, tears sprang to her eyes. “It’s humiliating,” she said, her voice falling low. “I’ve felt only two things since the day they sent me away, and that is either quite lost or quite angry, and at present, I am choosing angry.”

“Nevertheless, there is no need to resort to violence.”

“Do no’ condescend to me, sir!”

Mr. Bain reached into the interior of his coat and withdrew a handkerchief, which he held out to her. “It doesna follow that because I find your actions rash that I am condescending,” he sniffed.

She took the handkerchief. “Why must men always believe they are superior to women in intellect and deed?”

“Oh, I donna know,” he drawled, and folded his arms across his chest. “What in blazes would bring you back here, where you are clearly no’ wanted, with no hope of having your side heard? Only a fool would take such a risk. A risk, I might add, that might have seen you killed, aye? And for no possible gain. It defies logic.”

Maura rolled her eyes and blew her nose. “I would no’ have been killed, Mr. Bain. But if there was the slightest possibility, do you really think I would risk my life to speak to Sorcha? I donna care what she thinks of me, on my word! And if you’re so clever, why did you no’ tie me up or keep watch over me? Why did you assume you knew how I’d respond to your decision for my fate?”

-->

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

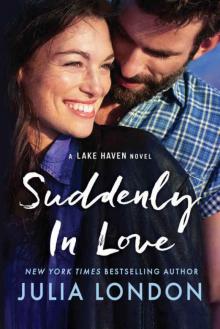

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)