- Home

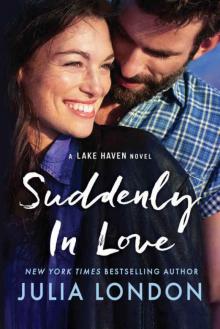

- Julia London

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) Page 7

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) Read online

Page 7

“I’ll get on that, Mom.”

The contents of his mother’s cocktail glass had tipped to the right along with her, and had come dangerously close to spilling on the expensive Persian carpet. For as long as Harry could remember, his mother never touched a drop of alcohol . . . until Sunday. On Sundays, she would start in the morning and go until Dad poured her into bed in the evening.

“Where is our girl?” she’d asked, looking around him.

“She’s not coming, Mom,” he’d said. “We, ah . . . we’re taking a break.”

He had then endured his mother’s wailing as if she’d just heard for the first time that the Titanic had sunk. Over the course of a horrible luncheon, he’d told his family—his mom and dad and his sister Hazel—what had happened.

Harry thought back to the bright spring Sunday. His family had been shocked and wounded by the split, naturally, because they’d all assumed Melissa would be part of the family, and had come to think of her as one of their own. It had been tough for Harry to listen to their sorrow. Especially when he was feeling that same sorrow and hadn’t really processed it.

He’d been sad, and wounded, and despondent . . . but there also had been a tiny part of him that had felt the tiniest bit of relief. He had goals in life, and he’d begun to feel smothered by Melissa’s expectations, his parents’ expectations, and the growing demand that he somehow fit everyone’s idea of what he ought to be when none of it matched what he wanted to be.

He’d explained to his family that the relationship had been complicated, and that there was no one “thing” that had done it.

“Oh, Harry!” his mother had groaned when he’d said all he could say, her drink sloshing around again. “I can’t believe you broke up! Is it the apartment? I know it’s that apartment. Dosia! Dosia, are you going to serve any time soon?” she’d shouted at the family’s long-time maid.

Dosia had appeared from the kitchen with a platter of chicken breasts, her long gray hair in a bun on top of her head, and her wide hips covered in the gray shift of a maid’s uniform. “Hello, Mr. Harry.”

“Hello, Dosia.” Dosia had a little room behind the kitchen where she watched reality TV and knitted sweaters for her grandkids in Poland. Once a year, over the Christmas holiday, his parents paid for her trip back home. He had fond memories of lying on Dosia’s bed when he was a boy, watching television with her on the many nights his parents were out.

“I’m very sorry, Mr. Harry,” she’d said.

“Thank you.”

“Well?” his mother had demanded. “Is it the apartment?”

“Mom, come on.” He had felt suddenly exhausted in that moment. “It’s a lot of things,” he’d said.

“Can we eat?” Hazel had asked, consulting her watch. “I have to make rounds this afternoon.” His sister had a residency in psychiatry at Mount Sinai. She was two years older than Harry and rarely dated that he knew of. She’d often said she was married to her job. She had dark corkscrew curls and deep blue eyes. Harry had never understood why men didn’t fall at her feet, but if they did, Hazel kept quiet about it. Maybe she was just a lot smarter than he was.

“Yes, let’s eat,” Harry’s dad had said, reaching for the chicken. Dosia had appeared again, this time with asparagus and some sort of potato dish. She’d set them down and then very quietly removed the setting that had been laid for Melissa.

Harry’s mother poured wine into her glass, which she’d placed beside her noon cocktail, and passed the bottle to Harry. “I know it’s the apartment,” she’d said again. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes brightened by the alcohol. “I told you this would happen when you decided to quit your job. I told you it would all go to hell, all that you’d worked for.”

Actually, what she’d said when Harry quit his job was that she and Dad had wanted him to become partner at his engineering firm and join them in country club memberships, fundraisers for important causes, and Upper East Side living. “That’s why we sent you to a good school,” she’d said then.

“Beth,” his dad said at the lunch table. “Don’t be so hard on him. Harry has accomplished a lot.”

His mother had snorted. “He’s doing manual labor, Jack. That’s not what we raised our son to do. We raised him to be a great man. And Melissa wants a good life,” she’d said as she helped herself to a tiny spoonful of scalloped potatoes. “She deserves that.”

“I would give her a good life,” Harry had said defensively.

But his mother had rolled her eyes. “She is the perfect girl for you, Harry, and if you can’t see that, there is no hope for you.”

“I know it’s hard for you, Mom. But I want something different than Lissa wants. And I’m selling the apartment to buy a crane.”

“Well,” his father had said as Dosia returned with a plate of fruits and cheeses, “maybe we should reconsider loaning him the money, Beth, so he doesn’t have to sell the apartment.”

“Oh, Jack.” His mother had sighed with the perpetual disappointment she held for Harry’s father. “You know that’s not possible. Harry would have been partner now if he’d stayed at Michaelson’s. And you want to buy him a crane?”

“He wants something different,” his father had said patiently. “He’s told us that more than once. It’s his life.”

“It’s okay, Dad,” Harry had said. “The apartment is already sold.” He’d not been willing to have that argument again, not that day, not when he was feeling so down. He’d had the same argument with his mother many times, had told her how he hated the idea that he had to have some fancy title in order to gain her approval. That he was pursuing the vision of his life he’d had since he was a kid.

“But what he wants is not something that will put a decent roof over his head,” his mother had said, and had lifted her wine glass to her lips. “He’ll end up living in some awful part of Long Island.”

“You don’t know that,” Harry had said, bristling. “You know what, Mom? You wanted me to be partner. Well, I’m the sole partner in Westbrook Bridge Design and Construction. If that’s not good enough for you, I’m sorry.”

“And I’m sorry that we really can’t support that, Harry,” his mother had said in an incredibly patronizing tone. “We didn’t send you to Cornell University so you could build bridges.”

“What the hell did you think a degree in civil engineering was about?” he’d asked incredulously.

“I thought it was about a partnership in a prestigious firm!”

Harry had looked helplessly to his father, but his father had lowered his gaze, his focus on his food. There had been no point in even pretending that his dad could help him out. Jack Westbrook, a robust, healthy, sixty-five-year-old man, was a complete slave to his wife. That’s because he’d married a woman with a lot of money and she’d controlled the purse strings all of their marriage. For all of Harry’s life, his dad had played second fiddle to his wife.

But what had really riled Harry was that neither of them could encourage the monumental effort he was making to become a self-made man. “Yeah, okay,” he’d said. He’d lost his appetite and his patience, and he was not going to sit there and take his mother’s disdain or his father’s impotence on top of losing Melissa. So he’d put aside his linen napkin and had stood up.

“Sit down, Harry,” his mother had said.

“No thanks, Mom. Have a good afternoon.” He’d started for the door.

“Wait—you’re leaving?” Hazel exclaimed.

“Yeah, I’m leaving.”

“Harry, wait!” Hazel had clambered to her feet.

“For God’s sake, Harry, don’t run off in a snit,” his mother had said impatiently. “We’re only trying to help.”

“Help?” He’d angrily whirled back around. “You’re not helping, Mom, you never help! You want a title? I’ve got a title for you—”

“Don’t say it,” Hazel had whispered frantically as she’d reached him.

“Beth—”

“Don’t tel

l me to give him the money, Jack,” she’d snapped.

“I didn’t ask you for money!” Harry had roared. He’d made that mistake only once and he would never make that mistake again. What did they take him for? He’d pivoted about and strode for the door.

“Wait, wait,” Hazel had begged him, grabbing his arm as she squeezed out into the hall with him. “Jesus, will you wait?”

Harry had huffed. But he’d paused. “What?” he’d snapped.

Hazel had glared at him. “Don’t treat me like I’m your mother.”

“Sorry. But I’m not staying, Hazel. Don’t try to talk me into it. I’ve had a rough week and I don’t want to listen to her—”

“I want to offer you the money,” Hazel had blurted.

Harry blinked. “For what?”

“For your crane! I can lend you the money.”

Harry hadn’t been able to keep from smiling, and had fondly wrapped his arms around her shoulders and hugged her. “Thanks, Hazel. But the last thing I want is to take any money from my big sis. And besides, even though I know you’re pulling in some bucks these days, I doubt you have the kind of money I need.”

“How much?” she’d asked.

“A million.”

Hazel had pushed back from him, her eyes full of shock. “Holy shit! For a crane?”

“Not all for a crane,” he’d explained. “That’s operating costs, heavy equipment, manpower . . . I need that in the bank before I go and bid as a contractor on one of these state projects. I’ve been subcontracting pieces of the bridge. Now I want the whole thing. That’s why I’m selling my apartment.”

Hazel had groaned. “Look, don’t be mad at Mom. She doesn’t want to see you sink your inheritance into a business that might not work out, you know?”

His sister was referring to the money they’d inherited from their grandfather. Harry had used his share to buy his apartment. “I know,” he said. “But Grandpa built Carlington Industries from the ground up. I think he’d understand. Actually, I think he would tell me there’s no gain without risk and to go for it.”

“I miss him. Come on, Harry, come back in. Mom will be passed out in an hour, and you and Dad and I can watch the Mets.”

“Nah,” he’d said, and had tweaked Hazel’s nose. “I’m gonna run.”

“Please don’t tell me you’re going to drown your sorrows in beer.”

“No,” Harry had scoffed as he started for the elevators, punching the down button. “I’ve got the kind of sorrows only a single malt whiskey can touch.” He’d winked at Hazel and stepped into the elevator car.

He did have a couple of whiskies that night. They did nothing to ease the hurt in him.

He hadn’t been back to see his parents since.

He damn sure wasn’t going back now with his tail between his legs, leaking money and still trying to win a bid on his own, all because a woman with less-than-stellar housekeeping skills had barged uninvited into his life. He could imagine how that conversation would go. No, I couldn’t stay at my friend’s house because this woman stacks dishes in the sink and leaves them there.

No way, man. He was too strong for this. He would make this work somehow. He’d treat it like boot camp—keep his nose down, do his work, and ignore her.

Harry got out of his truck and slammed the door, suddenly determined. He’d go to work, eat out, and never come out of that mother-in-law suite. He didn’t need a kitchen or a pool. He just needed a place to sleep.

Eight

Lola figured she might as well get to the coffee shop, seeing as how her roommate had rudely awakened her and made her so mad she couldn’t go back to sleep. She didn’t know what she was going to do with him yet—ignore him? Annoy him to death? Turn him in? One thing was certain—she wasn’t going to let him interfere with her plans to meet Birta Hoffman.

Determined to forget his awful personality, which totally ruined his super-sexy physique, she hopped on her bike at half past eight. The drivers on Juneberry Road were in such a hurry to get to work, and whipped around her so fast that twice she almost lost her balance.

On Main Street, Lola locked her bike to a rack beneath a maple tree, removed her tote bag with her laptop from the bike’s basket, and entered the Green Bean Coffee Shop, where she discovered the drivers who’d almost mowed her down were now standing in line for coffee. She took her place at the end, wedging herself between the door and the creamer station.

As the line inched along toward the barista, Lola scanned the crowded tables in search of Birta Hoffman. She had no doubt she’d recognize her—in all of Birta’s author photos, she had signature long black hair with a thick streak of white that framed her face. She looked like an author. On the book jacket of her latest novel, Inconsequential, she was wearing a strand of mala beads around her neck. She held a pair of glasses as if she’d just taken them off to speak to the viewer. She wore leather and silver bracelets on her wrist and stared at the camera with a contemplative gaze, as though she were willing to discuss the meaning of life with you.

There was no such woman in this coffee house. Maybe Birta knew about the morning rush and preferred to wait it out. Well, Lola had brought her laptop so she could work. If Birta didn’t show up today, Lola would come again tomorrow.

When it was finally her turn, Lola ordered a caramel latte.

The young man behind the counter didn’t acknowledge that he’d even heard her. He said nothing at all, just scratched around his nose ring before he took her debit card and ran it, then placed a paper cup in line with others. She spent another five minutes crowded against the wall before her drink appeared. She gratefully accepted it and sipped.

And winced.

That was no caramel latte. She didn’t know what it was, but she didn’t like it. She made a move toward the counter to tell them, but a man in a business suit behind her sighed loudly, as if she were intentionally trying to annoy him by not getting out of the way. So she reflexively stepped away from the counter with the drink that was not hers, for which she’d paid five dollars, thank you very much. It wasn’t even sweet.

The tables were completely full, but she spotted one across the room tucked up against the wall with a pair of coffee cups and two empty pastry plates. Lola began to weave her way through the tables for it, holding her bag aloft so as not to bonk anyone in the head with it. And just as she was about to break free of the obstacle course of human bodies, wooden chairs, and people’s bags on the floor, a girl wearing floral tights and a very short skirt appeared from nowhere and plunked her computer bag down on the table.

Lola gaped at the girl, who was now texting on her phone. She spared Lola a glance. “Sorry,” she said.

Lola was going to stand up for herself and demand this table, but the girl took a phone call, and Lola’s resolve deflated. She turned around in defeat, and in doing so, her bag bumped against a table. She heard the cups rattle and grabbed the edge of the table. “I’m so sorry.”

“Don’t apologize! It’s super crowded in here. It’s a wonder tables and cups aren’t flying.”

Lola looked at the woman who had said those words. She looked to be Lola’s age. She had a book in one hand, a plate with the crumbs of her breakfast at her elbow. She had frizzy brown hair, was pleasingly plump, and wore a silver chain around her neck from which dangled a silver candy wrapper charm. Lola liked her dancing brown eyes and snowy white teeth.

“You can sit here if you like,” she said, indicating the empty chair.

“Would you mind?” Lola asked gratefully.

“Not at all. Better you than that guy,” she said, nodding toward a man with dreadlocks who looked as if he’d been sleeping on the beach. “I’m Mallory Cantrell, by the way.” She pushed the extra chair out for Lola.

“Hi,” Lola said, and juggled her coffee and her bag so she could extend her hand. “I’m Lola Dunne.”

“Nice to meet you, Lola Dunne! Pretty name. My cousin had a dog named Lola,” Mallory said, reaching for Lola’s cup.

“Yeah . . . I get that a lot,” Lola said, and gratefully relinquished her cup, plopped onto the empty chair, and dropped her bag by her feet with a sigh of relief.

“Are you new to town?” Mallory asked.

Lola had thought about this question and what her response would be if asked, and said confidently, “I’m staying at my friend’s house.”

“Oh, where’s that, on the lake? It’s gorgeous right now, isn’t it? Everything is blooming.”

“Yep, on the lake. Out on Juneberry Road,” Lola added absently.

“Hey, my aunt lives on Juneberry. Small world, huh? So who’s your friend? I probably know her. I’m a year-rounder.”

“A what?”

Mallory laughed. “That’s what we locals call ourselves. Year-rounders. Who did you say your friend was?” she asked again.

“Sa . . .” Lola thought twice about what she was about to say, and at the last moment, changed that S sound to a Z. “Zach Miller.” That would be safer, she thought. According to Sara, Zach hadn’t been a regular at the lake in a few years.

But Mallory gasped with delight and said loudly, “Zach Miller! Well hello, Lola Dunne! Very nice to meet Zach’s friend.”

Shit. Shitshitshit. “You know him?”

“I don’t really know him,” Mallory said to Lola’s great relief. “Not well, anyway. But we’ve met a couple of times at different functions. He’s very generous to the Lake Haven Foster Kids’ Project. But you know how generous he is.”

Zach Miller? Lola tried not to look shocked and glanced down just in case her expression gave her away, because the man Sara had so vividly described was a narcissist dickhead who rarely showed his face in East Beach. Not a generous man contributing to a charity for foster kids.

“He’s modest,” Mallory said, mistaking Lola’s reaction. “Is he in town? I’d love to say hello.”

“No, no,” Lola said quickly. “No, I don’t think he’ll be out this summer. Lots going on, you know.” She glanced away guiltily. She wondered what Humorless Harry said when people asked him where he was living. Oh, right—he was so charming he probably didn’t have any friends.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)