- Home

- Julia London

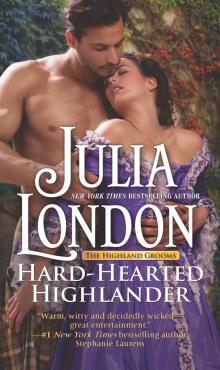

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel Page 7

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel Read online

Page 7

Down the table, Lord Kent’s voice rose with the unmistakable hoarseness of too much drink. “Enough of nursemaids and Highlanders and whatnot. Tell me now, laird, how does your trade fare? I might as well inquire, as it will all be in the family soon enough.” He laughed.

Miss Catriona Mackenzie, seated next to her father and across from Lord Kent, choked on a sip of wine, coughing uncontrollably for a moment.

“Well enough,” the laird said quietly, and leaned to one side to rub his daughter’s back.

“Aye, well enough when we avoid the excise men,” Rabbie Mackenzie said, and chuckled darkly.

That remark was met with stunned silence by them all. Bernadette didn’t know what he meant, really, but his family seemed mortified.

Lord Kent seemed intrigued.

Suddenly, Captain Mackenzie laughed, and loudly, too. “My brother means to divert us,” he said jovially. “He is master at it, so much so that we donna know when he teases us.”

Bernadette did not miss the look that flowed between brothers, but Captain Mackenzie continued on. “I am reminded of an occasion we sailed to Norway, Rabbie. You recall it, aye?”

“I’ll no’ forget it,” his brother said.

The captain said, “We sailed into a squall, we did, the seas so high we were pitched about like a bairn’s toy. A few barrels of ale became unlashed and washed over the side with a toss of a mighty wave.”

Bernadette’s stomach lurched a tiny bit, the memory still fresh in her legs and chest of roiling seas.

“What a tragedy for you all to lose your ale,” Lord Kent scoffed.

“Aye, but it was,” the captain agreed with much congeniality, politely ignoring his lordship’s tone. “Rabbie and I didna have the heart to tell our crew of the loss, no’ with two days at sea ahead of us, aye? When the seas calmed, and the men looked about for their drink, I said to Rabbie, ‘We’ll be mutinied, mark me.’”

Lord Mackenzie smiled, amused by that.

“Rabbie said, ‘No’ on my watch, braither.’ When I asked what he meant to do, then, he said he didna know, aye? But he’d think of something.”

“Oh, aye, he’d think of something, would he?” Catriona said laughingly.

“What happened?” Avaline asked eagerly, held rapt by the captain’s tale.

“He gathered the lads round, and told them a fantastic yarn of the sea serpent who stole their ale.” Captain Mackenzie leaned forward and said in a low voice, “Now the lads, they’ve been a sea for a long time, they have, and they donna believe in sea monsters. But Rabbie was so convincing in his telling of it that more than one began to crowd to the middle of the main deck, fearing one of the serpent’s arms would appear to pull them into the sea along with their drink.” He laughed and settled back in his chair. “They didna fret about their ale, no’ after that tale. My brother spoke with such confidence they couldna help but believe him.”

Bernadette wondered after an entire ship of men who would fall prey to such a ridiculous tale. And yet, across from her sat a pretty, cake-headed girl, eyes wide with delight as she listened to Captain Mackenzie. Fortunately, Avaline seemed to have forgotten all about the ogre sitting next to her.

And yet it hardly mattered that Avaline’s attention had been diverted, for the ogre appeared quite content to be forgotten. He sat back in his seat, his expression unreadable as everyone around him laughed at that ridiculous story. But his hand was curled into a tight fist against the table, and Bernadette had the distinct impression he was holding himself in check. From what? Was he angry? Did he dislike his brother’s amusing tale?

“Shall we retire to the sitting room?” Lady Mackenzie asked, and stood.

The ogre stood, and, rather miraculously, he held Avaline’s chair out so that she might rise. Avaline didn’t seem to notice the polite gesture at all—her gaze was on Captain Mackenzie and she hurried to his side to ask him something about the story he’d just told as they began to make their way out of the small dining room.

Once again, Bernadette followed behind the rest of them, only this time, she had company. Rabbie Mackenzie fell in beside her, his hands clasped at his back. He said nothing, and certainly neither did Bernadette. She was aware of how much his body dwarfed hers. She felt unusually small next to him, and imagined how helpless Avaline would feel beside him. She tried not to picture their wedding night, but it was impossible once the thought had crowded into her head—Bernadette could see him, tall and broad and erect...

Goodness, but she imagined that in very vivid detail, and carefully rubbed her neck, trying to erase the heat that suddenly crawled into her skin.

The room in which they’d gathered was another sitting room, with two settees and a few armchairs, and a few spare dogs eager to greet everyone who entered the room.

At the far end of the room was a harpsichord. Bernadette sighed softly to herself. She knew where this was headed. They would have the obligatory demonstration of Avaline’s “abilities.” Avaline was terrified of performing before others, and frankly, Bernadette was terrified for her. She had little real talent for it, and the harder she tried, the worse she sang. It was a cruel fact that women of Avaline’s birthright were expected to excel in all things domestic—in managing their household, in needlework, in art and song. She was also expected to demonstrate how pleasingly accommodating she was by showing an eagerness to perform at the mere invitation. And woe to the woman who did not excel at singing, for she couldn’t escape her duty to display her so-called wares.

Bernadette’s talent was in playing the harpsichord. She, too, had been born to this perch in life...but she’d fallen from it.

“Here then, allow my daughter to regale us with a song,” Lord Kent said almost instantly, without any regard for his daughter’s feelings on the matter, or her lack of talent. He was well aware how it frightened Avaline to stand before anyone and sing—the good Lord knew it had been a source of contention between them many times before this particular evening.

“Miss Holly, you will accompany her,” his lordship decreed.

All heads swiveled about to where Bernadette stood just inside the door, the ogre at her side. She bristled at the command, could feel the heat of shame flood her cheeks. As if she were a trained monkey like the one she’d once seen in a London market.

“Go on, then,” Mr. Mackenzie said. “Donna draw this out any more than is necessary.”

“You have nothing to fear in that regard,” she muttered, and walked to the front of the room—for Avaline’s sake, always for Avaline’s sake—wiping her palms on the sides of her gown as she went. She sat on the bench before the harpsichord, glanced up at an ashen Avaline and whispered, “Look above their heads, not at them. Pretend no one is here, pretend it is a music lesson.”

Avaline nodded stiffly.

Bernadette began to play. Avaline began to warble. She held her hands clasped tightly at her waist, her nerves making her sing sharp to the music. At last, the poor girl finished the song to tepid applause. The ladies, Bernadette noticed, were shifting restlessly in their seats. And in the back of the room, standing exactly where she’d left him, stood Rabbie Mackenzie. His head was down, his arms folded, his expression one of pure tedium.

But the song was done, and Avaline moved immediately to sit, as did Bernadette, but Lord Kent, slouching in his chair, his eyes half-open after the amount he’d drunk, waved her back. “Again, Avaline. Perhaps something a bit livelier that won’t put us all asleep.”

Avaline’s shoulders tensed. She turned to Bernadette, her eyes blank now, her soul having retreated to that place of hiding. Bernadette managed a smile for the poor girl. “The song of summer,” she said softly. “The one you like.”

Avaline nodded. As she moved to take her place next to the pianoforte, and Bernadette played the first few chords, she looked up to see if Avaline was ready, an

d noticed, from the corner of her eye, that Avaline’s fiancé had exited the room. How impossibly rude he was! It made her so angry that she hit a wrong chord, startling Avaline. “I beg your pardon,” Bernadette said, and began again.

This time, when the song mercifully ended, it was Captain Mackenzie who rose to see Avaline to a seat, complimenting her on her singing as he did.

The evening dragged on from there. Bernadette stood near a bookcase, pretending to examine the few titles they had there, impatient for the evening to come to an end. She was trying desperately not to listen to Lady Kent and Avaline attempt to converse with the Mackenzie women about the blasted wedding.

At long last, his lordship rose, signaling to his party. They could at last quit this horrible place and return to Killeaven.

None of the Mackenzies entreated them to stay, but eagerly followed them out like so many puppies—with the notable exception of Avaline’s fiancé, of course—and called good-night as they climbed into the coach. Even his lordship took a seat inside the coach, having instructed a man to tether his horse to the back of it. As soon as they rolled out of the bailey, he turned a furious glare to Avaline. “You are a stupid, vapid girl!” he said heatedly. “You have no knowledge of how to woo a man! What am I to do if he cries off? What will I do with you then?”

“I beg your pardon, Father, but I tried—”

“You asked after his favorite governess!” her father shouted at her, spittle coming out of his mouth with the force of his voice. “Haven’t you the slightest notion how to bat your eyes? And you,” he said, swinging his gaze around to Bernadette.

“Me?”

“Yes, you! You’re a wily woman, Bernadette. Can you not teach her to be less...vapid?” he exclaimed, flicking his wrist in the direction of his daughter. “Can you not teach her how to lure a man to her instead of cleaving the line and letting him sink away?”

“The man is entirely disagreeable—”

His lordship surged forward with such ferocity that his wig was very nearly left behind. “I don’t care if he is Satan himself. The marriage has been agreed to and by God, if he cries off because of her,” he said, jabbing his finger in the direction of Avaline, “I will take it out of her hide.”

Avaline began to cry.

Her father fell back against the squabs and sighed heavily, as if he bore the weight of the world on his shoulders. “What have I done to deserve this?” he said to the ceiling. “What sin have I committed that you give me a miserable wife without the ability to give me a son, and a stupid twit for a daughter?”

Needless to say, by the time the old coach had bounced and plodded and bumbled along to Killeaven, the entire Kent family was in tears.

If Bernadette had been presented with a knife during that drive, she would have gladly plunged it into her own neck, just to escape them all.

CHAPTER SIX

AVALINE WAS FINALLY ALONE. She was never alone; there was always someone about to tell her what to do, what to say, how to behave.

It had been a very long day and a draining evening at Balhaire. Her eyes and her face were swollen from sobbing, and her mother’s attempt at making a compress had only angered her. She’d sent her mother from the room, had locked the door behind her.

Now, Avaline had no tears left in her. What she had was a hatred of her father that burned so intently she felt ashamed and concerned God would strike her dead for it. She hated how her father treated her, but she hated worse how she sobbed when he said such awful things to her. She was quite determined not to, but she could never seem to help herself.

What she told him was true—she had done her best this evening. She had tried to engage that awful man as Bernadette said, had tried to be pleasant and pretty and quiet. Nothing worked. What was she to do? He stared at her with those dark, cold eyes. His jaw seemed perpetually clinched. He rarely spoke to her at all, and when he did, every word was biting. He hated her. Which was perfectly all right as far as Avaline was concerned, because she hated him, too, hated the very sight of him.

And the singing! Avaline groaned at the humiliation she had suffered. Couldn’t her father hear with his own ears that she wasn’t good enough to hold entire salons captive? He blamed her for her lack of talent and had once accused her of intentionally singing poorly only to vex him. What on earth would possess her to humiliate herself before others merely to annoy her father?

Avaline rolled onto her side and stared at the window, left open to admit a cool breeze. She couldn’t see beyond it, but she imagined she could hear the sea from here. It was probably only a night breeze rustling the treetops, but she wanted to imagine the sea.

She thought about running away. She thought about stowing aboard Captain Mackenzie’s ship. She pictured him now, with his kind smile, his hair so prettily streaked by endless days on the vast sea. He was so completely appealing! One night, as they sailed up the coast to the Highlands, Avaline had been too restless and too warm in the cabin she’d shared with Bernadette, and had waited until Bernadette was asleep before venturing onto the deck.

She’d been gazing up at the stars, so brilliant that they felt within reach. The captain had been surprised to stumble upon her there. “You must be cold, aye?” he asked in that lilting voice of his, and shrugged out of his coat and draped it around her shoulders. Then he pointed out some of the stars to her—Orion, Sirius and Polaris. He told her he’d been sailing since he was a “wee lad” and once he’d begun, he’d never left the sea. “Aye, I love it as if it was a bairn,” he’d said. “It changes every day.”

Avaline wanted to be somewhere that changed every day. She wanted to talk about stars and clouds and sea swells. She wanted to love something so fiercely that she couldn’t leave it. She wanted to look into the captain’s clear blue eyes and see him smile, and never, ever, think of his awful, wretched brother again.

She rolled onto her back and wondered what Captain Mackenzie would do if he found an English woman hiding on his ship. Perhaps even in his cabin, as no one would think to look for her there. Would he return her to father? Or would he take her in his arms and kiss her and promise her a life of adventure? Wouldn’t that be very romantic?

Why couldn’t it have been him, the man who knew the names of stars and always had a smile for her? Why was it his awful brother? Why, God, why?

Avaline wished she could confess her true feelings to Bernadette about Captain Mackenzie, but that was impossible—Bernadette would force her to forget Captain Mackenzie. She would dog Avaline, and she would know when Avaline was thinking of him. Bernadette always seemed to recognize what Avaline would do before Avaline realized it herself.

She sighed wearily, feeling quite heavy of heart for her seventeen years. She could feel sleep creeping into her body, pushing her down into unconsciousness, and as she drifted away, she imagined sneaking onboard the Mackenzie ship, imagined what the captain’s private quarters must look like, and how comforting it would be to have all his things around her. She imagined the moment Captain Mackenzie entered the quarters and found her there...

CHAPTER SEVEN

THEY MEET EVERY afternoon and walk along the cliff above the cove, speaking of everything and nothing, laughing at secret jokes. Their fingers are entwined except in those moments when Rabbie leans down, picks up a rock and hurls it out to sea. Sometimes, he carries her on his back so that the hem of her arasaid will not get wet. Sometimes, they go down to the beach, and she picks up a stick and draws the shape of a heart with their initials.

They mean to be married. They don’t know when, and they have kept this promise to each other a secret. These are uncertain times—whispers of rebellion and treason seem to slip through the hills on every breeze.

On a particularly cool afternoon, Rabbie returns Seona to her family home and sees the horses there, still saddled. Inside, he hears the voices of men. Seon

a’s mother, a large woman with a welcoming smile, appears, but today she seems unusually fretful. As they walk past the room where Seona’s father and brothers are gathered, Rabbie sees the men who have come. Buchanan, Dinwiddie, MacLeary. All of them Jacobites, all of them known to conspire against the king. This is treacherous ground, and Rabbie glances at Seona. She doesn’t appear to notice the men. She is smiling, telling her mother about the ship they spotted passing along the coast with a flag of black and red. He doesn’t know if Seona understands what her father and brothers are about.

* * *

THE FOLLOWING TWO days after that interminable dinner, with singing so atrocious that Rabbie wished he was deaf, passed in a haze of restlessness. His thoughts kept going back to that evening and the moments he’d stood at the back of the music room, endeavoring—and failing—to grasp how he might possibly make a life with the lass.

Perhaps his father was right. Perhaps he ought to put her in at Killeaven and leave her there.

That dinner was intended to establish harmony between two families that would, in a matter of days, be forever tied by matrimony, but Rabbie couldn’t bear the thought of even bedding her. He’d escaped unnoticed from the music room, and had gone in search of drink stronger than wine.

His path had taken him to the kitchen. He’d heard voices as he approached, and figured the servants were cleaning up after the supper. He could hear Barabel’s deep voice instruct someone in Gaelic, “Have a care with the plate, lass. We’ve precious few of them now.”

He walked into the kitchen and just over the threshold, he froze. Barabel was instructing the MacLeod children. The lass glanced up at him and smiled. The lad scarcely made eye contact before turning back to his task of drying pots.

“Aye, Mr. Mackenzie, may I help you?” Barabel asked in Gaelic.

“Whisky,” he said, his voice rough with an emotion he hadn’t even realized he was holding.

Barabel disappeared into the adjoining storeroom to fetch it.

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)