- Home

Page 8

Page 8

A Royal Kiss & Tell

A Royal Kiss & Tell You Lucky Dog

You Lucky Dog The Devil in the Saddle

The Devil in the Saddle The Trouble with Honor

The Trouble with Honor Tempting the Laird

Tempting the Laird The Secret Lover

The Secret Lover A Light at Winter’s End

A Light at Winter’s End The Charmer in Chaps

The Charmer in Chaps Homecoming Ranch

Homecoming Ranch Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5)

Jack (7 Brides for 7 Soldiers Book 5) A Courtesan's Scandal

A Courtesan's Scandal Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel

Hard-Hearted Highlander--A Historical Romance Novel The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy

The Complete Novels of the Lear Sister Trilogy The Last Debutante

The Last Debutante Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4)

Suddenly Single (A Lake Haven Novel Book 4) Seduced by a Scot

Seduced by a Scot Highlander Unbound

Highlander Unbound Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2)

Suddenly Dating (A Lake Haven Novel Book 2) The Bridesmaid

The Bridesmaid The Seduction of Lady X

The Seduction of Lady X One Mad Night

One Mad Night Extreme Bachelor

Extreme Bachelor The Scoundrel and the Debutante

The Scoundrel and the Debutante The Revenge of Lord Eberlin

The Revenge of Lord Eberlin American Diva

American Diva The Lovers: A Ghost Story

The Lovers: A Ghost Story The Hazards of Hunting a Duke

The Hazards of Hunting a Duke Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River)

Return to Homecoming Ranch (Pine River) The Perils of Pursuing a Prince

The Perils of Pursuing a Prince Highlander in Love

Highlander in Love The Devil Takes a Bride

The Devil Takes a Bride Devil in Tartan

Devil in Tartan Wild Wicked Scot

Wild Wicked Scot Snowy Night with a Highlander

Snowy Night with a Highlander One Season of Sunshine

One Season of Sunshine Summer of Two Wishes

Summer of Two Wishes All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor

All I Need Is You aka Wedding Survivor Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel

Sinful Scottish Laird--A Historical Romance Novel Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3)

Suddenly Engaged (A Lake Haven Novel Book 3) Highlander in Disguise

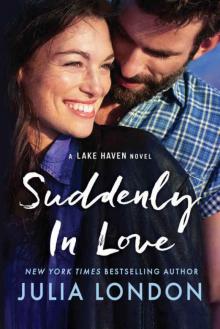

Highlander in Disguise Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)

Suddenly in Love (Lake Haven#1)